the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Two different perspectives on heatwaves within the Lagrangian framework

Volkmar Wirth

Although heatwaves are one of the most dangerous types of weather-related hazards, their underlying mechanisms are not yet sufficiently understood. In particular, there is still no scientific consensus about the relative importance of the three key processes: horizontal temperature transport, subsidence accompanied by adiabatic heating, and diabatic heating. The current study quantifies these processes using an Eulerian method based on tracer advection, which allows one to extract Lagrangian information. For each grid point at any time, the method yields a decomposition of temperature anomalies into the aforementioned processes, complemented by the contribution of a pre-existing anomaly. Two different approaches for this decomposition are employed. The first approach is based on the full fields of the respective terms and has been established in prior research. In contrast, the second approach is based on the anomaly fields of the respective terms, i.e. deviations from their corresponding climatologies, and is introduced in this study. The two approaches offer two distinct perspectives on the same subject matter. By analysing two recent heatwaves, it is shown that the two decompositions yield substantial differences regarding the relative importance of the processes. A statistical analysis indicates that these differences are not coincidental but are characteristic of the respective regions. We conclude that the Lagrangian characterization of heatwaves is a matter of perspective.

- Article

(8880 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Heatwaves stand out as one of the most perilous weather-related hazards. They threaten natural ecosystems and society in many ways (e.g. Perkins, 2015; Horton et al., 2016; Barriopedro et al., 2023, and references therein). Their frequency and intensity are projected to increase in the course of global warming (e.g. IPCC, 2021), likely posing an even greater danger to humanity in the future. The socioeconomic importance of heatwaves is thus abundantly clear.

Far less clear, however, are the mechanisms that determine the formation of heatwaves. While it is well known that heatwaves in the extratropics are invariably associated with large-scale upper-tropospheric ridging (Sousa et al., 2018) or anticyclonic flow (e.g. Stefanon et al., 2012; Zschenderlein et al., 2019), often in the form of atmospheric blocking (e.g. Pfahl and Wernli, 2012), a lack of consensus about how exactly air masses with anomalously high temperatures form in this large-scale setting remains.

Three processes are believed to play a role in the context of heatwaves: horizontal advection of warm air (e.g. Screen, 2014; Harpaz et al., 2014; Garfinkel and Harnik, 2017; Sousa et al., 2019; Garfinkel et al., 2024), adiabatic warming in subsiding air (e.g. Bieli et al., 2015; Zschenderlein et al., 2019), and diabatic heating near the surface (e.g. Miralles et al., 2014; Schumacher et al., 2019). The large-scale setting seems to be conducive to all three processes, and often more than one process has been considered important (e.g. Quinting and Reeder, 2017; Hochman et al., 2021; Röthlisberger and Papritz, 2023). The question still under debate is to what extent each of the individual processes contributes to the formation of heat extremes.

A novel quantitative approach to address this question has recently been proposed by Röthlisberger and Papritz (2023). This approach sees the decomposition of a temperature anomaly at a given location into (distinct) contributions from each of the three individual processes. More precisely, the approach quantifies the effect of horizontal advection across climatological temperature gradients, the combined effects of vertical advection across climatological temperature gradients and adiabatic warming, and the effect of parcel-based diabatic heating. Like many studies focussing on the processes within heatwaves (Harpaz et al., 2014; Bieli et al., 2015; Zschenderlein et al., 2019; Schielicke and Pfahl, 2022), the temperature anomaly decomposition approach by Röthlisberger and Papritz (2023) adopts the Lagrangian framework. This is a natural framework for studying the processes under consideration since the laws of dynamics and thermodynamics inherently apply to air parcels. In the Lagrangian framework, individual fluid parcels can be tracked, their physical properties can be identified, and any temporal changes in these properties can be assessed. Therefore, the Lagrangian framework enables a physically meaningful quantification of desired quantities such as adiabatic and (parcel-based) diabatic heating.

Given that most common atmospheric models work in the Eulerian framework, obtaining Lagrangian information about the flow requires some extra effort. Often, backward-trajectory models are employed for that purpose (e.g. LAGRANTO; see Sprenger and Wernli, 2015, or HYSPLIT; see Stein et al., 2015). In this study, however, we refrain from calculating trajectories and instead opt for an alternative approach. We will use the method of tracer advection proposed in Mayer and Wirth (2023) to extract the necessary Lagrangian information. The strength of this method is that it provides the required Lagrangian information directly in the form of global gridded fields available at any time step. Most importantly, this makes it quite straightforward to calculate climatologies for every grid point on a global Eulerian grid. We will take advantage of this and, for the first time, present climatologies of the contributions from horizontal transport, vertical transport, and diabatic heating. Based on these climatologies, we will show that the original temperature anomaly decomposition proposed by Röthlisberger and Papritz (2023) may not be as unique as it appears at first sight. We will thus offer a fresh perspective on the relevance of the individual processes to the formation of heatwaves.

In this paper, we perform a temperature anomaly decomposition (Sect. 2.1), akin to the method proposed by Röthlisberger and Papritz (2023). To this end, we apply a novel technique to extract the required Lagrangian information (Sect. 2.2). We then use this setup to analyse two recent heatwaves (Sect. 3.1) and to relate the contributions from the individual processes to their long-term averages (Sect. 3.2). Based on these long-term averages, we suggest an alternative decomposition based on anomaly fields (Sect. 3.3). Finally, we complement the two case studies with a short statistical analysis (Sect. 3.4). We close the paper with a brief discussion (Sect. 4) and a concluding summary (Sect. 5).

2.1 Lagrangian θ′ decomposition

In this study, we aim to quantify the extents to which horizontal transport, vertical transport, and diabatic heating contribute to the formation of temperature anomalies. For this purpose, we examine anomalies in potential temperature θ′, which we decompose from a Lagrangian perspective into the aforementioned processes. We opt for potential temperature instead of temperature as our metric because potential temperature is materially conserved in adiabatic flow, rendering it more convenient for theoretical considerations.

We consider the potential temperature anomaly of an air parcel located at grid point x at time t. This anomaly, , represents the deviation of the potential temperature θ(x,t) from its climatological average :

Taking the material derivative on both sides,

and applying Euler's relation (in pressure coordinates),

to the last term on the right-hand side of Eq. (2), one obtains

where v denotes the horizontal wind, ∇h is the horizontal gradient, p is pressure, and ω is the vertical wind in pressure coordinates. Finally, we accumulate the contributions from each of the individual terms in Eq. (4) along the trajectory of the air parcel and obtain

where t0 is the start time of the integration, t is the time of interest, and is the temperature anomaly at the start time. The integrals in Eq. (5) represent Lagrangian integrals; i.e. they accumulate information along the trajectory of the air parcel that happens to be located at location x at time t.

Equation (5) decomposes a potential temperature anomaly of an air parcel into five contributions: (1) horizontal transport across climatological horizontal temperature gradients; (2) vertical transport across climatological vertical temperature gradients; (3) diabatic heating of the air parcel along its trajectory; (4) local changes in the climatological potential temperature, including seasonality and the diurnal cycle; and (5) the initial temperature anomaly of the air parcel at the start time of the integration. The above decomposition closely follows the approach by Röthlisberger and Papritz (2023), except that they used temperature instead of potential temperature and chose the initial time t0 such that the temperature anomaly is zero at that time.

The integrals on the right-hand side of Eq. (5) can be extended to start at −∞ if, at the same time, the integrand is multiplied by a Heaviside function that jumps from 0 to 1 at time t0. For reasons that will become clear later, we prefer to use an exponential function instead of a Heaviside function. As shown in Appendix A, this leads to the following equivalent formulation for , namely

with

Effectively, the contributions from the different processes in the first four terms of Eq. (6) are multiplied by a weighting factor with λ>0; thus, W decreases exponentially as the integration variable t′ goes backward in time. The decay time related to the exponential weighting is governed by the parameter λ and effectively determines the timescale of accumulation. It is typically chosen to be on the same order of magnitude as t−t0 in Eq. (5). On the other hand, the different processes occurring in the residuum term R are multiplied by 1−W, such that R essentially contains contributions that occurred during the more distant past. The residuum R in Eq. (6) corresponds to the initial potential temperature anomaly in Eq. (5), although they are not identical. Like in Eq. (5), the integrals in the above equation represent the accumulation of processes in air parcels along their trajectories. The only difference is that now the accumulation is more gradually spread over time, such that the contributions fade away more gradually rather than suddenly at time t0. The decomposition in Eq. (6),

is the basis for the analysis in our paper. In the following, we are going to refer to the first three terms as the “process terms”, comprising the contributions to the temperature anomaly θ′ from (1) horizontal transport θhor, (2) vertical transport θver, and (3) diabatic heating θdia. The fourth term, θsea, containing the seasonality, is much smaller than all other terms and will be neglected in the remainder of this paper. The last term, θpre, corresponds to the residuum R and will be referred to as the pre-existing potential temperature anomaly in the following. It reflects the accumulation of the three process terms from earlier times along the parcel's trajectory, i.e. up to about λ−1 before the point in time considered, t. In other words, θpre is analogous to the initial potential temperature anomaly of a trajectory of length λ−1.

2.1.1 Eulerian tracer advection with relaxation

The integrals in the θ′ decomposition are obtained through the method of tracer advection (Mayer and Wirth, 2023). This method is tailored to provide Lagrangian information that is aggregated over time. The method offers Lagrangian information in the form of gridded fields available at any time step, i.e. throughout the four-dimensional space–time domain. In theory, the same information could be obtained by calculating trajectories. However, gathering Lagrangian information about the full atmospheric volume at many time steps requires the computation of a very large number of trajectories. In contrast, the tracer method eliminates the need for this procedure and directly provides the time-aggregated information required by this study. We feel that this makes the method very convenient for our application. Note that the fields generated by the tracer method cover the entire global domain, but only a small portion of the available data is presented in this study. With the available data, the analysis could be carried out for any other region in the world.

The tracer method is based on the offline advection of passive tracer fields and includes a relaxation term. As a result, one obtains accumulated Lagrangian information at each point of an Eulerian grid at each time step, namely

where S(t′) is some source term, and λ is the relaxation constant. Note that the term on the right-hand side represents a Lagrangian integral and features the same exponential weighting as in our decomposition (6). That is, indeed, the primary reason why we introduced the exponential weighting earlier in our θ′ decomposition approach.

To obtain values for δ(x,t), the tracer method numerically solves the partial differential equation

with the initial condition

In this equation, δ is a three-dimensional (tracer) field that is advected by the three-dimensional wind u and that is, in addition, subject to some source term S. The exponential weighting present in Eq. (8) stems from the linear relaxation term −λ δ included on the right-hand side of Eq. (9). The primary advantage of the relaxation is that it gradually diminishes the influence of past data on the fly, enabling us to obtain time-continuous Lagrangian information much more efficiently than without relaxation.

When S can be expressed as the material rate of change in some quantity a, i.e. , Eq. (9) can be reformulated into

in combination with

Instead of δ itself, the field ψ now constitutes the tracer field, and the source term S is implicitly included in the relaxation term.

A separate tracer is required for each term in the θ′ decomposition. To compute θhor, θver, and θsea, we use Eq. (9), with the source term S as , , and , respectively. For example, in order to compute θhor, we numerically integrate the following equation:

The resulting solution is then equivalent to

In contrast, θdia is computed via Eqs. (11) and (12). That is, we set a to θ(x,t) and numerically integrate the following equation:

in combination with

The solution is equivalent to the desired integral,

Using Eqs. (11) and (12) instead of Eq. (9) for the computation of θdia has the significant advantage of not requiring any information about the parcel-based diabatic heating rate, which is often unavailable or not fully available.

Finally, θpre is computed as the residuum from the actual potential temperature anomaly θ′ and the other four terms:

For details about the tracer method and its implementation, the interested reader is referred to Mayer and Wirth (2023).

2.1.2 Data

This study is based on ERA5 reanalysis data (Hersbach et al., 2020) for the period of 2010 to 2022. We use global data on model levels (Hersbach et al., 2017), with a horizontal resolution of 1° and a temporal resolution of 3 h. In the vertical dimension, we take every second model level between model levels 136 and 50, which cover the entire troposphere and parts of the lower stratosphere. Whenever we show or refer to data on pressure levels, we provide data that have been linearly interpolated from model levels to a set of pressure levels. For the relaxation constant, we use λ−1 = 7 d throughout this study.

The variables used are the zonal wind u, the meridional wind v, the vertical velocity that corresponds to the vertical coordinate η, the pressure–coordinate vertical velocity ω, and pressure p. Potential temperature θ is computed from p and temperature T as

with and p0=1013.25 hPa. The climatological average in Eq. (6) depends on both the time of the year and the time of the day. It is obtained for each day of the year by computing a time-of-day-specific temporal average over the 13 years considered, followed by a 31 d smoothing; effectively, each climatological value is an average over 13 × 31 = 403 individual values. Note that the period and the procedure chosen to compute the temperature climatology are similar to those used in the study by Hotz et al. (2024), with which we compare our results later on.

The θ′ decomposition is obtained every 3 h and aggregated to yield daily means. Whenever we use the term “near-surface”, we refer to the average over the lowest 50 hPa above the surface.

3.1 A first look at two recent heatwaves

In the following, we are going to present the results of our decomposition for two recent heat events, namely the Pacific Northwest heatwave in 2021 and the UK heatwave in 2022. In particular, we discuss the evolution of the near-surface θ′ as well as the time-mean vertical θ′ structure. In doing so, we follow the analysis of Hotz et al. (2024), who applied the temperature decomposition of Röthlisberger and Papritz (2023) to the aforementioned heatwaves. In particular, we use the same definition of the heatwave regions (49–59° N, 125–115° W for the Pacific Northwest heatwave; 49–59° N, 6° W–4° E for the UK heatwave) and episodes (27 June to 1 July 2021 for the Pacific Northwest heatwave; 16 to 20 July 2022 for the UK heatwave) to enable a straightforward comparison between their results and ours.

3.1.1 The Pacific Northwest heatwave

In 2021, a severe heatwave struck the Pacific Northwest, marking unprecedented temperatures in Canada and the USA. Many cities experienced all-time maximum-temperature records being broken by several degrees (e.g. Philip et al., 2022; White et al., 2023). The heatwave was associated with a strong upper-tropospheric quasi-stationary anticyclone (e.g. Philip et al., 2022; Neal et al., 2022) fuelled by warm-conveyor-belt outflow from an upstream cyclone (e.g. Schumacher et al., 2022; Neal et al., 2022; White et al., 2023; Oertel et al., 2023; Röthlisberger and Papritz, 2023; Papritz and Röthlisberger, 2023; Hotz et al., 2024). For this event, we will now showcase the results of our decomposition.

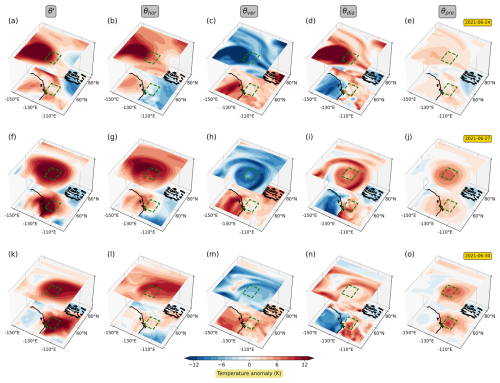

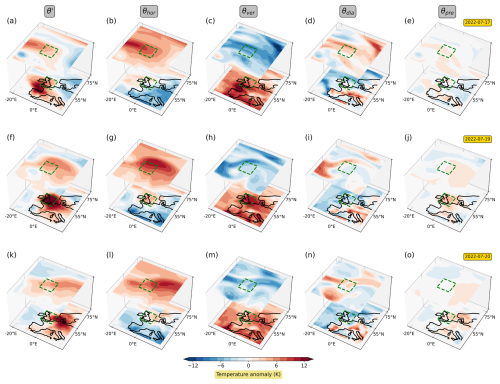

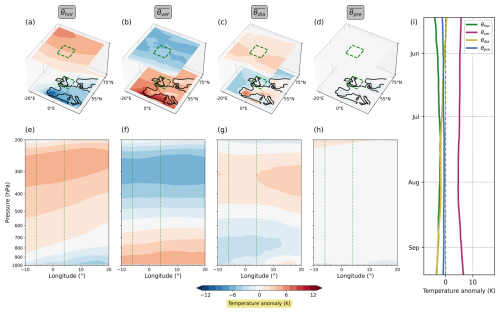

Figure 1Illustration of the three-dimensional structure of θ′ and its contributions from horizontal transport, vertical transport, diabatic heating, and the pre-existing anomaly for three selected dates (24, 27, and 30 July 2021). The upper layer depicts fields averaged between 300 and 400 hPa, and the lower layer depicts fields near the surface. The green rectangle indicates the Pacific Northwest heatwave region.

To start with, Fig. 1 illustrates the evolution of the heatwave by showing θ′ and its decomposition for 3 individual days during the heatwave. As already noted by previous authors (e.g. Neal et al., 2022; Hotz et al., 2024), the large temperature anomalies first appeared in the upper troposphere and only later emerged near the surface. Initially, a tongue of warm air intruded northward at upper levels (Fig. 1a; see Neal et al., 2022), and this can be associated with significant positive contributions from horizontal transport and diabatic heating (Fig. 1b and d), as well as a negative contribution from vertical transport (Fig. 1c). Such contributions would be expected in the context of warm-conveyor-belt outflow. Later, the air mass associated with the tongue started to form a spiral and became enclosed in the anticyclone (Fig. 1h and i). During the course of the event, the contribution from the pre-existing anomaly seemed to grow steadily (Fig. 1e, j, and o), which first occurred mostly in the upper troposphere and later also near the surface. At the same time, the contributions from horizontal transport, vertical transport, and diabatic heating decreased in the upper troposphere. This behaviour suggests an effective transfer of heat from the three process terms to the pre-existing term: what was initially classified as horizontal transport, vertical transport, or diabatic heating gradually turned into the pre-existing term. This sequence likely indicates that the large temperature anomalies present at the later stage were generated at least partly before or during the early stage of the heatwave. This interpretation is consistent with the findings by, e.g. Papritz and Röthlisberger (2023), who identify warm-conveyor-belt air streams associated with two upstream cyclones as the main heat source for this event.

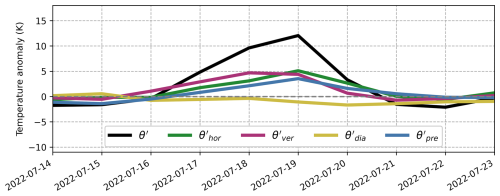

We next investigate the evolution of the near-surface θ′ over the course of the heatwave. To this end, we show time series of the individual θ′ terms near the surface, averaged over the core heatwave region (green box in Fig. 1). Figure 2 reveals that during the heat event, all four decomposition terms contributed positively to θ′, albeit with varying magnitudes. Throughout most of the event, the largest positive contribution from the three process terms was given by diabatic heating. The contribution from horizontal transport reached its maximum during the early phase and decreased throughout the course of the event, while the contribution from vertical transport was initially small and gradually increased as the heatwave progressed. Similarly, the pre-existing anomaly was initially small and grew steadily over the course of the event, until it finally made the largest contribution out of all the terms during the late stage of the heatwave. Overall, the evolution is similar to that shown by Hotz et al. (2024) (their Figs. 3i and 4). For example, there is agreement that the near-surface diabatic heating makes the largest contribution of the three process terms throughout the course of the heatwave, even if it is somewhat larger in Hotz et al. (2024) than here. Likewise, in both analyses, the contributions from horizontal and vertical transport swap rankings on 28 June in terms of their positive contribution to θ′.

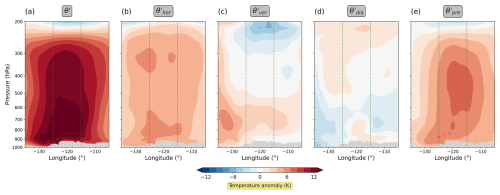

Figure 2Evolution of the near-surface potential temperature anomaly θ′ and its decomposition into contributions from horizontal transport, vertical transport, diabatic heating, and the pre-existing anomaly during the Pacific Northwest heatwave. The time series have been obtained by averaging the different terms over the lowest 50 hPa above the surface within the Pacific Northwest heatwave region.

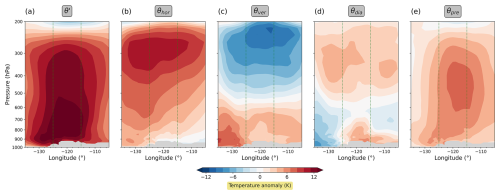

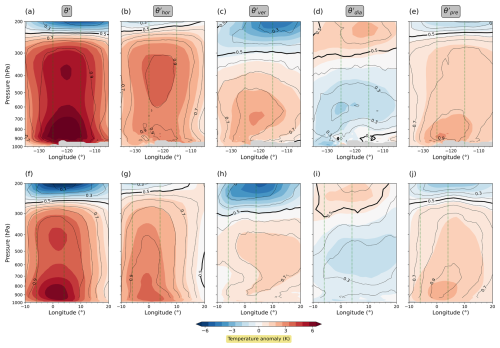

Finally, we present the time-mean vertical θ′ structure during the heatwave in Fig. 3. In essence, these plots show the same characteristics as discussed before, with the benefit of the full vertical resolution, but in a time-aggregated manner. The general structure of the time-mean vertical fields is, again, similar to the results in Hotz et al. (2024), even though there are differences in the exact values and some structural details. To be clear, we do not expect perfect agreement for two basic reasons: (1) we use potential temperature rather than temperature as our key variable, and (2) our decomposition includes the pre-existing anomaly, which does not exist in the formulation of Röthlisberger and Papritz (2023) due to their specific choice of t0. Item (1) can be expected to be an issue mostly in the upper troposphere where T and θ deviate substantially; in contrast, item (2) can generally be an issue throughout the atmosphere. During the episode considered, our term R in Fig. 3e maximizes in the middle troposphere. Note that this behaviour largely resembles the structure of the Lagrangian age shown by Hotz et al. (2024) (their Fig. 4b), consistent with our interpretation of R as the pre-existing anomaly.

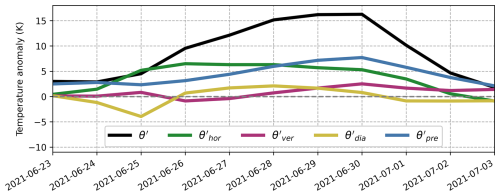

Figure 3The 5 d mean (27 June–1 July 2021) vertical cross-section showing the θ′ decomposition during the Pacific Northwest heatwave. Fields are latitudinally averaged between 49 and 59° N. The panels show (a) the potential temperature anomaly θ′, (b) the contribution from horizontal transport, (c) the contribution from vertical transport, (d) the contribution from diabatic heating, and (e) the contribution from the pre-existing anomaly. The topography is shown in grey. The two vertical green lines in each panel indicate the longitudinal extent of the Pacific Northwest heatwave region.

Overall, our results for the Pacific Northwest heatwave are in good agreement with those of Hotz et al. (2024), suggesting that both methods are able to quantitatively capture the key processes of temperature anomaly formation and their relative importance.

3.1.2 The UK heatwave

We now turn to analysing the UK heatwave in 2022. In comparison to the temperature anomalies reached during the Pacific Northwest heatwave, the UK heatwave was less severe. Nonetheless, it was sufficiently strong to break several all-time maximum-temperature records in multiple cities across the UK.

Again, we first illustrate the evolution of the heatwave by showing θ′ and its decomposition for 3 individual days (Fig. 4). Like the Pacific Northwest heatwave, the UK heatwave was also associated with anticyclonic flow, albeit with a much more transient character. High-temperature anomalies first occurred in the southwestern parts of Europe, then intensified and crossed the UK before shifting downstream (Fig. 4a, f, k). As with the Pacific Northwest heatwave, a tongue of warm air initially appeared in the upper troposphere, accompanied by a significant positive contribution from horizontal transport (Fig. 4b), and some positive contribution from diabatic heating (Fig. 4d) as well as negative contribution from vertical transport (Fig. 4c). Presumably, this is again a signature of warm-conveyor-belt outflow, although the features are overall less coherent than in the Pacific Northwest case. Later, the tongue stretched around the core heatwave region, but unlike the Pacific Northwest heatwave, it did not develop a spiralling pattern.

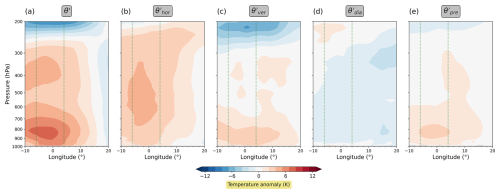

Figure 4Illustration of the three-dimensional structure of θ′ and its contributions from horizontal transport, vertical transport, diabatic heating, and the pre-existing anomaly for three selected dates (17, 19, and 20 July 2022). The upper layer depicts fields averaged between 300 and 400 hPa, and the lower layer depicts fields near the surface. The green rectangle indicates the UK heatwave region.

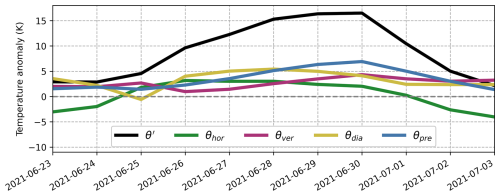

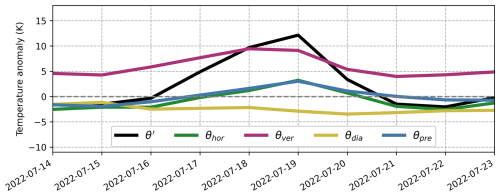

The evolution of the near-surface θ′ decomposition (Fig. 5) reveals that the positive contribution from vertical transport was the highest throughout the event, jointly followed by the contributions from horizontal transport and the pre-existing anomaly. The contribution from diabatic heating, on the other hand, was negative. This is a noticeable difference from the Pacific Northwest heatwave. Our results align quite well with those found by Hotz et al. (2024): they also attribute the largest positive contribution to vertical transport, and in both cases, the diabatic heating did not make any substantial positive contribution. One noticeable difference is the contribution from vertical transport before and after the heatwave, which in our analysis is considerably larger.

Figure 5Evolution of the potential temperature anomaly θ′ and its decomposition into contributions from horizontal transport, vertical transport, diabatic heating, and the pre-existing anomaly during the UK heatwave. The time series have been obtained by averaging the different terms over the lowest 50 hPa above the surface within the UK heatwave region (6° W–4° E, 49–59° N).

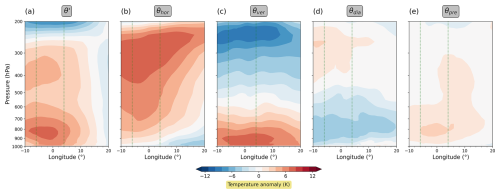

We finally look at the time-mean vertical structure of the event's θ′ decomposition (Fig. 6). Once again, we find small quantitative differences between our analysis and the analysis of Hotz et al. (2024), while the overall patterns of the fields are similar in both analyses. Again, for the reasons mentioned earlier, we do not expect perfect agreement between these two analyses. All in all, both analyses lead to essentially the same conclusions, and this suggests that the exact design of the temperature anomaly decomposition and its implementation is of minor importance.

Figure 6The 5 d mean (16–20 July 2022) vertical cross-sections showing the θ′ decomposition during the UK heatwave. Fields are latitudinally averaged between 49 and 59° N. The panels show (a) the potential temperature anomaly θ′, (b) the contribution from horizontal transport, (c) the contribution from vertical transport, (d) the contribution from diabatic heating, and (e) the contribution from the pre-existing anomaly. The two vertical green lines in each panel indicate the longitudinal extent of the UK heatwave region.

3.2 Long-term averages of the terms in the decomposition

We now present long-term averages of the θ′ decomposition for the two regions discussed above. Subsequently, this will allow us to adopt a novel perspective on the relevance of the different terms in the decomposition. We believe that this is an important step because, as we will see shortly, many of the features of the individual terms described above are part of the climatological behaviour and, therefore, may not be helpful in explaining an anomalous temperature.

The long-term averages of the terms in the θ′ decomposition are determined by calculating temporal averages for each individual day of the year, based on the period of 2010 to 2022. Subsequently, these day-specific temporal averages are smoothed using a 31 d running average. Note that this procedure is identical to the one used for the temperature climatology (see Sect. 2.1.2). The period to compute the long-term averages comprises (only) 13 years, which is admittedly shorter than the traditional definition of a climatological mean. However, we deliberately chose this relatively short period of time to ensure that the climatological mean calculated mostly reflects the current state of the changing climate. This way, the anomalies we present are considered anomalous compared to today’s conditions rather than to those from the past. In the end, the chosen length of the period was a compromise between the robustness of the statistics and the stationarity of the climate.

We start with the long-term averages in the Pacific Northwest region (Fig. 7). Here, the contribution from horizontal transport (Fig. 7a and e) is positive in the upper troposphere and mostly negative close to the surface. This behaviour aligns well with the characteristics of the zonal-mean Lagrangian circulation (e.g. Townsend and Johnson, 1985; Iwasaki, 1989; Juckes, 2001), which exhibits poleward motion in the upper troposphere (implying a positive contribution from horizontal transport) and equatorward motion near the surface (implying a negative contribution from horizontal transport). Deviations from this overall behaviour are most likely due to local land–sea contrasts in temperature. The long-term average of the contribution from vertical transport (Fig. 7b and f) exhibits behaviour opposite to that of the horizontal transport, namely a negative contribution in the upper troposphere and a positive contribution near the surface. From a statistical point of view, this makes perfect sense, as air masses close to the surface can only originate from higher above (implying a positive contribution from vertical transport); just below the tropopause, the situation is more or less opposite, to the extent that the tropopause is a barrier to vertical transport. The contribution from diabatic heating (Fig. 7c and g) is positive in the upper troposphere, possibly due to latent-heat release within frequently occurring warm conveyor belts within the north Pacific storm track region. Near the surface, the contribution from diabatic heating is positive over the land and negative over the ocean, which is most likely related to the influence of surface heat fluxes. The contribution from the pre-existing anomaly (Fig. 7d and h) is small throughout the whole troposphere. All terms show little variation over the summer season (Fig. 7i), except for the diabatic one. The latter exhibits a range of about 5 K, with positive values until mid-August and negative values thereafter. Arguably, this behaviour reflects the seasonal cycle in solar radiation.

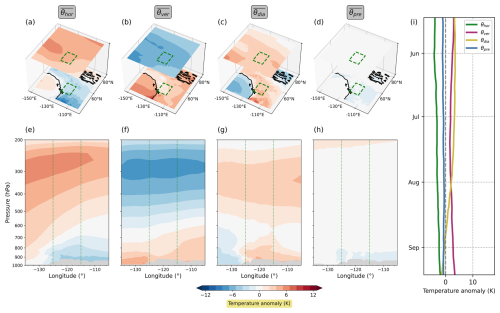

Figure 7The long-term average (2010–2022) of the θ′ decomposition for the Pacific Northwest. Panels (a) to (h) depict the long-term averages for the time period during which the Pacific Northwest heatwave happened; i.e. they show the 5 d averages of the daily climatologies from 27 June to 1 July. Panel (i) shows the evolution of the long-term average near-surface θ′ decomposition during the summer season, averaged over the Pacific Northwest heatwave region. The three-dimensional plots in panels (a) to (d) are analogous to those in Fig. 2b–p, and the vertical cross-sections in panels (e) to (h) are analogous to those in Fig. 3b–e.

The long-term averages from the UK region (Fig. 8) exhibit mostly the same characteristics as those from the Pacific Northwest. The only notable difference manifests near the surface. Here, the contribution from diabatic heating is significantly lower in the UK region compared to the Pacific Northwest, ranging from near zero to even slightly negative values. Presumably, this feature can be attributed to the fact that the UK is surrounded by the ocean, which implies that air masses located over the UK have a larger chance of originating over the ocean and, therefore, are less exposed to sensible-heat fluxes over land.

Figure 8The long-term average (2010–2022) of the θ′ decomposition for the UK region. Panels (a) to (h) depict the long-term averages for the time period during which the UK heatwave happened; i.e. they show the 5 d averages of the daily climatologies from 16 to 20 July. Panel (i) shows the evolution of the long-term average near-surface θ′ decomposition during the summer season, averaged over the UK heatwave region. The three-dimensional plots in panels (a) to (d) are analogous to those in Fig. 5b–p, and the vertical cross-sections in panels (e) to (h) are analogous to those in Fig. 6b–e.

3.3 A second look at the two heatwaves from an anomaly-based perspective

We now continue with the analysis of whether and to what extent the terms in the decomposition were anomalous with respect to their corresponding climatologies. To this end, we compute the anomaly fields of the individual decomposition terms and use these in our alternative decomposition. More specifically, we define the anomaly field of a variable ψ as the deviation ψ′ from its long-term average , i.e.

Using this definition, the original θ′ decomposition (7) can be expressed as

where each term is now represented as the sum of its climatological mean and a deviation from this mean. Taking the time average on both sides turns Eq. (21) into

Given that the time-averaging scheme is linear, this equation can be rewritten as

Assuming further that the time-averaging scheme obeys the rules of Reynolds averaging, i.e.

Eq. (23) can be simplified to

Substituting Eq. (25) into Eq. (21) yields the following new θ′ decomposition:

In contrast to the original θ′ decomposition (7), which relies on full (absolute) fields, the new θ′ decomposition (26) is based on anomaly fields. Both formulations are mathematically sound; they differ in that they offer two distinct perspectives on the same subject matter. Note that our daily climatologies imply some 31 d smoothing, such that the assumption of a Reynolds average is, strictly speaking, not satisfied. However, as we will see below, the corresponding error is negligible.

In the following, we will show that the anomaly-based perspective on the θ′ decomposition leads to substantial differences regarding the relative importance of horizontal transport, vertical transport, and diabatic heating compared to the perspective in terms of the full fields.

3.3.1 The Pacific Northwest heatwave revisited

Once again, we begin by discussing the Pacific Northwest heatwave and first look at time-mean vertical cross-sections from the anomaly-based perspective (Fig. 9). In the upper troposphere, the contributions from horizontal transport, vertical transport, and diabatic heating are substantially smaller in magnitude than their contributions in terms of the full fields. As a consequence, only the horizontal transport, together with the pre-existing anomaly, still yields a substantial positive contribution to θ′. In the lower troposphere, positive contributions from vertical transport and diabatic heating persist, albeit smaller in magnitude. In contrast, the contribution from horizontal transport changes in such a way that it now provides positive contributions throughout the entire lower troposphere, constituting the largest contribution to θ′ alongside the pre-existing anomaly.

Figure 9Same as Fig. 3, but the θ′ decomposition terms are now depicted as deviations from their long-term averages.

Second, we show the evolution of the near-surface θ′ decomposition from the anomaly-based perspective (Fig. 10). Like before, all terms yield mostly positive contributions, but the magnitudes differ. Most notably, the diabatic heating no longer dominates among the three process terms; instead, its contribution is significantly smaller than that of horizontal transport throughout the episode. As before, the contribution from vertical transport increases throughout the evolution of the heatwave but no longer overtakes the contribution from horizontal transport at any point in time. Only the pre-existing term manages to overtake the contribution from horizontal transport at some point, albeit 2 d later than before. Note that the slopes of the individual curves are nearly identical in both decompositions because the time rate of change in the corresponding climatology terms is very small (see Fig. 7i). This means that both decompositions yield almost the same results if one aims to diagnose the rate of change in the individual terms. However, in the current paper, we focus on the temperature anomalies themselves rather than their tendencies.

Figure 10Same as Fig. 2, but the θ′ decomposition terms are now depicted as deviations from their long-term averages.

The change from the original to the anomaly-based perspective swaps the roles, broadly speaking, of the diabatic heating and the horizontal transport regarding their contributions to the temperature anomaly θ′. The new perspective takes into account that normally the contribution from horizontal transport is negative, such that a slight positive contribution to the original decomposition actually represents a rather strong positive contribution to the anomaly-based decomposition. In contrast, the diabatic heating, which makes a strong contribution to the original decomposition, turns out to be less important in the new decomposition because it is just a little stronger than usual.

3.3.2 The UK heatwave revisited

Finally, we show the anomaly-based perspective on the UK heatwave. The new decomposition for the time-mean vertical structure (Fig. 11) also shows substantial differences with respect to the original decomposition. In particular, now the contribution from vertical transport in the lower troposphere does not dominate the decomposition any longer; instead, the contributions from horizontal transport and the pre-existing anomaly are of similar magnitudes. The same behaviour is revealed in the near-surface time series in Fig. 12.

Figure 11Same as Fig. 6, but the θ′ decomposition terms are now depicted as deviations from their long-term averages.

3.4 Statistics for heat extremes in the two heatwave regions

In a final step, we now want to generalize the above results by looking at statistics about heat extremes in the two regions considered. In this section, we will focus on the anomaly-based decomposition.

We choose the following simple definition for a heat extreme. We calculate the spatial average of the near-surface potential temperature anomaly in the respective region for each day between 15 May and 15 September and subsequently select the days on which the 90th percentile is exceeded. This procedure results in 162 d, which we refer to as hot days from the respective region. Our statistical analysis is then based on these selected hot days.

To start with, Fig. 13 shows vertical cross-sections of θ′ and its (anomaly-based) decomposition averaged over all hot days in the respective region. In both regions, near-surface heat extremes are most notably associated with an anomalous positive contribution from horizontal transport throughout the whole troposphere (Fig. 13b and g), contributing around +3 K on average. Moreover, as indicated by the contour lines, at least 80 % of these extremes show an anomalous positive contribution from horizontal transport up to the tropopause. Additionally, in the lower half of the troposphere, the contribution from vertical transport (Fig. 13c and h) is anomalously positive by about 1–2 K on average, reflecting downwelling in anticyclonic flow during heatwaves. The overall contribution from diabatic heating (Fig. 13d and i) tends to be anomalously negative (around −1 K), presumably due to anomalous radiative cooling in strongly subsiding air masses. Pre-existing anomalies (Fig. 13e and j) of 1–2 K on average seem to be nearly always present during heat extremes.

Figure 13Vertical cross-section displaying statistical parameters of θ′ and its decomposition (anomaly-based perspective) for hot days in the Pacific Northwest region (a–e) and in the UK region (f–j). Colours depict the mean, whereas lines depict the fraction of data points that has a positive sign. Fields are latitudinally averaged between 49 and 59° N. The two vertical green lines in each panel indicate the longitudinal extent of the respective region on which the selection of hot days was based.

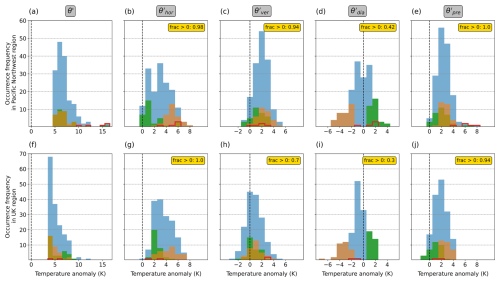

Next, we focus on the near surface and examine the distributions of the near-surface θ′ decomposition across all hot days in the respective regions (Fig. 14, blue histograms). Most striking is that the distribution of the contribution from horizontal transport is (nearly) exclusively in the positive range of values in both regions (Fig. 14b and g). This means that (almost) every hot day in the two regions is associated with an anomalous positive contribution from horizontal transport. Similarly, the distribution of the vertical transport also shows a clear shift towards positive values (Fig. 14c and h), indicating that hot days are usually (94 % or 70 %, respective to the Pacific Northwest or the UK) associated with an anomalous positive contribution from vertical transport. Likewise, the contribution from the pre-existing anomaly is typically positive (Fig. 14e and j).

Figure 14Histograms of occurrence frequency of the near-surface θ′ and its (anomaly-based) decomposition for hot days in the Pacific Northwest region (a–e) and in the UK region (f–j). The histograms are based on area mean values. Blue bars depict all data points. Green bars mark those data points that exceed the 80th percentile in diabatic heating, and orange bars mark those data points that are below the 20th percentile in diabatic heating. Red bars denote data points belonging to the heatwaves in 2021 (Pacific Northwest) and in 2022 (UK), respectively. The labels in the top-right corner of each panel give the respective fractions of positive values.

In contrast, the distribution of the diabatic heating is shifted towards negative values, indicating that hot days tend to be associated with less diabatic heating than average. At first glance, this fact may appear paradoxical, given that hot days are typically characterized by cloud-free skies and intense insolation, which may give rise to strong surface fluxes. However, one needs to keep in mind that our contributions represent an accumulation over the past few days of the parcel's trajectory, such that the local processes at the parcel's final destination do not necessarily play the dominant role. Substantial surface sensible heating at the parcel's final location will result in a large contribution from diabatic heating only if the parcel is close to the surface for a substantial length of time; otherwise, the surface sensible heating will not have enough time to heat the parcel. As indicated by a larger-than-usual contribution from vertical transport (Fig. 14c and h), this may not be the case here. Moreover, strong insolation and associated warm soil can only result in anomalously strong transfer of heat from the surface to the atmosphere if at the same time the atmosphere itself is not substantially warmer than usual. However, the latter seems to be the case here. Most air masses have been unusually warm in their recent past (e.g. Fig. 14e and j), which thus suggests an anomalously weak transfer of heat from the surface to the atmosphere.

In fact, the above reasoning is consistent with our results from Fig. 14. Apparently, air masses that have undergone unusually strong diabatic heating (indicated by the green bars) are often linked to anomalously small contributions from horizontal transport; on the other hand, the air masses that have undergone unusually weak diabatic heating (indicated by orange bars) tend to be associated with anomalously large contributions from horizontal transport. The same qualitative behaviour, albeit less pronounced, can be observed for vertical transport and the pre-existing anomaly, respectively.

It is interesting to contrast this general statistical behaviour with the situation observed in the Pacific Northwest heatwave. During that episode, clearly positive diabatic heating was observed despite strongly positive contributions from horizontal transport (red bars in Fig. 14b and d). This is consistent with other work suggesting that dry soil contributed to the Pacific Northwest heatwave (e.g. Schumacher et al., 2022; Li et al., 2024). Dry soil can enable unusually strong sensible-heat fluxes despite an already warm atmosphere.

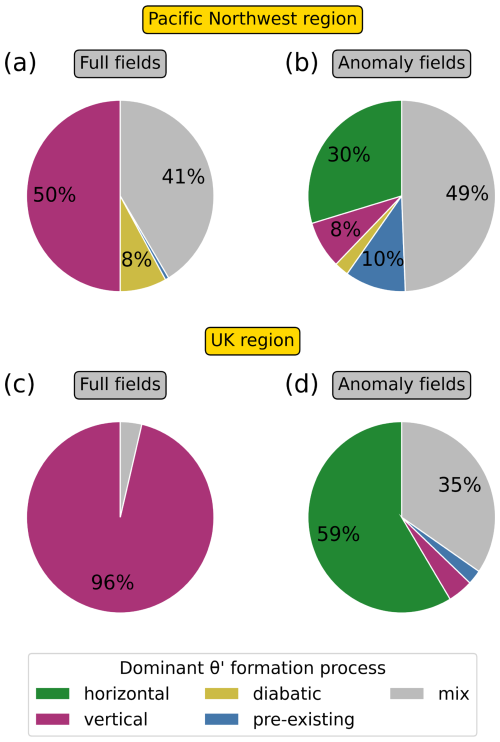

Finally, Fig. 15 presents an overview of how frequently each of the θ′ decomposition terms emerges as the dominant one (see figure caption). We provide results for both decompositions to highlight the contrasts in the θ′ decomposition in terms of the full fields versus the anomaly fields. Examining the θ′ decomposition through the full fields (Fig. 15a) reveals that in the Pacific Northwest region, vertical transport can be identified as the dominant process in 50 % of all hot days, followed by the diabatic heating in 8 % of all hot days. These proportions change drastically when the anomaly-based perspective is adopted (Fig. 15b). Now, it is the horizontal transport – never identified as dominant in the previous perspective – that most frequently emerges as the dominant process. The same behaviour but even more pronounced can be observed in the UK region (Fig. 15c and d). Note that the results may be sensitive to the precise definition of dominant, so the exact numbers may not be interpreted too literally. Nevertheless, the stark qualitative differences apparent in Fig. 15 underscore how strongly the Lagrangian characterization of heatwaves depends on the perspective.

Figure 15Pie charts displaying the relative frequency of the dominant near-surface θ′ formation processes for hot days during summer in the Pacific Northwest region (a, b) and in the UK region (c, d). A single process is considered dominant if it contributes at least 1.5 times as much as the second-highest term. If no single process is identified as dominant, the day is counted as “mix”. The pie charts are based on area mean values. In panels (a) and (c), the pie charts are based on the θ′ decomposition in terms of the full fields, whereas in panels (b) and (d), the pie charts are based on the θ′ decomposition in terms of the anomaly fields.

One of the key findings of our study is that horizontal transport – if viewed from the anomaly-based perspective – makes a strong, if not the strongest, positive contribution to near-surface heat extremes in the regions examined. What we want to emphasize is that this result does not contradict previous studies that concluded that horizontal advection is negligible (e.g. Bieli et al., 2015; Zschenderlein et al., 2019). Instead, our finding should be viewed as an indication that different perspectives result in different interpretations, although the underlying physics remains the same.

For example, Bieli et al. (2015) analysed heat extremes over the British Isles and found “no substantial meridional transport associated with hot extremes and, in particular, no strong advection of air masses from southerly regions”. Naturally, they concluded from this finding that “horizontal advection of warm air to locations where its temperature represents a large positive deviation from the climatological mean is thus not the primary mechanism in the development of hot extremes”. However, based on their observation that air masses during colder days originate significantly further north compared to warm extremes, they could have just as reasonably concluded that horizontal advection is relevant for heat extremes in the sense that cold-air advection is weaker than usual. In this context, there seems to be no right or wrong; instead the conclusions drawn are a matter of interpretation or definition.

To be sure, the idea of comparing Lagrangian characteristics of hot air masses with average conditions has been proposed before. For instance, Schielicke and Pfahl (2022) examined variables such as air mass origin, adiabatic heating, and parcel-based diabatic heating for low-level air masses during heatwaves and contrasted them with values that would typically occur in summer. After an extensive analysis, they found no unusual subsidence or diabatic heating during heatwaves over the British Isles and concluded that enhanced transport from warm continental regions in the east is of primary importance for high temperatures. These findings are consistent with our results from the anomaly-based θ′ decomposition, which showed that horizontal transport from climatologically warmer regions contributes more on average than vertical transport and diabatic heating to a positive near-surface temperature anomaly in the UK region. The strength of our anomaly-based θ′ decomposition is that it provides a systematic and straightforward framework, while other approaches, like the one of Schielicke and Pfahl (2022), may be less generic.

In our method, there is one user-defined parameter, namely λ. In this study, we selected this parameter to be 7 d. We repeated the analysis with 3 d to examine the sensitivity of our results to the value of λ. In the decomposition in terms of the full fields, the contributions from horizontal transport, vertical transport, and diabatic heating were generally smaller in magnitude with 3 d compared to the analysis with 7 d. On the other hand, the contribution from the pre-existing anomaly was generally larger with 3 d compared to the analysis with 7 d. This behaviour can be broadly expected: the analysis with a smaller λ−1 captures a smaller fraction of the processes that are accounted for by the larger λ−1, attributing the rest to the pre-existing anomaly. In other words, contributions that are assigned to horizontal transport, vertical transport, or diabatic heating are more likely to be transferred to contributions from the pre-existing anomaly when a small value of λ is applied. However, and most importantly, in both heatwaves, the overall vertical structure of the decomposition terms was similar for both values of λ. Similarly, in the anomaly-based decomposition, only small differences between both values of λ occurred. This suggests that, overall, the exact value of λ is of secondary importance.

A further characteristic of our temperature diagnostics is that the pre-existing anomaly usually exhibits the same sign as the actual temperature anomaly. This pattern holds true for not only positive temperature anomalies (see heatwave examples and statistical analysis) but also negative temperature anomalies (not shown). At first glance, this behaviour might seem disappointing, as our method often fails to completely attribute the observed temperature anomaly to the three physical processes. On the other hand, the existence of a pre-existing anomaly may be the reflection of a very fundamental atmospheric property, namely its persistence. Persistence is a well-known phenomenon over a wide range of timescales and variables (e.g. Pelletier, 1997; Pelletier and Turcotte, 1997; Koscielny-Bunde et al., 1998). Persistence of temperature, for instance, means that warm days (or months or years) are, more often than not, followed by warm days and cold days by cold days. In other words, persistence means that a variable (e.g. temperature) exhibits autocorrelation. This autocorrelation is particularly strong on the synoptic timescale (e.g. Talkner and Weber, 2000; Eichner et al., 2003). Considering the autocorrelation of temperature, it is not surprising that the pre-existing anomaly tends to be (strongly) positive during heatwaves: if there is a large temperature anomaly present today, it is very likely that a temperature anomaly already existed in the vicinity a few days earlier. Therefore, we do not consider our pre-existing term and its behaviour as weaknesses of our method but rather consider it to be a term with genuine physical significance, providing, in some sense, true added value.

Lastly, it is important to acknowledge that Lagrangian methods are generally subject to errors (e.g. Stohl, 1998; Stohl et al., 2002; Mayer and Wirth, 2023). This caveat applies to our analysis just as much as it applies to most previous trajectory-based studies of near-surface heat extremes (e.g. Harpaz et al., 2014; Bieli et al., 2015; Zschenderlein et al., 2019; Spensberger et al., 2020; Catalano et al., 2021; Hochman et al., 2021; Schielicke and Pfahl, 2022; Röthlisberger and Papritz, 2023; Hotz et al., 2024). One prominent issue is the atmospheric boundary layer, where turbulent mixing and convection are particularly pronounced. These processes are not fully accounted for when simply using mean wind fields from reanalysis data. Nevertheless, we believe that Lagrangian analyses such as ours and previous ones do provide valuable information when carefully interpreted. For instance, we never show results for a single grid point but rather provide information that is aggregated over time or space. The premise is that this aggregation reflects the mean behaviour of real air parcels to a fair approximation. While this assumption may seem strong, questioning it would also cast doubt on the validity of most other trajectory-based studies. Moreover, presumably most of the air parcels spend at least some of their recent history in the free atmosphere, where uncertainties in Lagrangian information are likely to be much smaller.

In this paper, we analysed heatwaves from a Lagrangian perspective. Core to our Lagrangian analysis was a Lagrangian θ′ decomposition based on the T′ decomposition proposed by Röthlisberger and Papritz (2023). Our Lagrangian θ′ decomposition partitions a potential temperature anomaly at a given location into contributions from horizontal transport, vertical transport, diabatic heating, and a pre-existing temperature anomaly in order to quantify the relative importance of these processes for the formation of heatwaves.

To obtain the Lagrangian information required for the analysis, we used the method of tracer advection with relaxation introduced by Mayer and Wirth (2023). This sets us apart from the majority of other Lagrangian studies on heatwaves, as we do not rely on trajectory calculations. The tracer method offers the advantage that long periods of data can be processed efficiently, facilitating the computation of climatologies.

First, we applied a decomposition closely resembling the original decomposition by Röthlisberger and Papritz (2023). We presented the results of that decomposition for two recent heat events, namely the Pacific Northwest heatwave in 2021 and the UK heatwave in 2022. In this context, the preceding study of Hotz et al. (2024), who also used the decomposition by Röthlisberger and Papritz (2023), served as a template and reference. In both heatwaves, we observed that the upper troposphere experienced positive contributions from horizontal transport and diabatic heating, which were partly compensated by negative contributions from vertical transport. Near the surface, during the Pacific Northwest heatwave, diabatic heating dominated most of the event, whereas during the UK heatwave, vertical transport was clearly dominant. Overall, these results are consistent with the results of the reference study and differ only in details.

Next, we provided, for the first time, long-term averages of the respective terms in the temperature anomaly decomposition. Interestingly, these averages showed similar characteristics to those observed during the heatwave periods. For instance, we observed that in the Pacific Northwest, air masses near the surface typically undergo significant diabatic heating, while in the UK, they experience a substantial positive contribution from vertical transport. This suggested that the notable positive contribution from diabatic heating (observed during the Pacific Northwest heatwave) or from vertical transport (observed during the UK heatwave) may not have been the decisive factor in the unusually high temperatures. Their contributions were substantial, although not exceptionally so. This motivated us to introduce a new temperature anomaly decomposition based on the anomaly fields of the respective terms.

Compared to the decomposition in terms of the full fields, the anomaly-based decomposition led to significant differences regarding the relative importance of the respective terms. For example, during the Pacific Northwest heatwave, diabatic heating no longer constituted one of the largest contributions but was clearly second to the contribution from horizontal transport. Similarly, in the UK heatwave, vertical transport no longer stood out as the sole dominant factor; instead, horizontal transport contributed significantly as well. Loosely speaking, near the surface, the horizontal transport thus emerged as the winner of this shift in perspective.

Finally, we complemented our study with a statistical analysis of hot days in the respective regions. Most notably, this analysis revealed that hot days in both regions consistently coincide with abnormally positive contributions from horizontal transport near the surface, often extending all the way to the tropopause. This suggests that anomalously positive horizontal transport can be regarded as a necessary (but possibly not sufficient) prerequisite for the formation of a heat extreme.

We believe that a lot can be learned from the anomaly-based decomposition, as it inherently provides an intuitive comparison to what can be expected from climatology. However, we are aware that even the anomaly-based decomposition, which may be regarded as an extension of the decomposition originally suggested by Röthlisberger and Papritz (2023), does not provide answers to all questions. For instance, while we can learn from the anomaly-based perspective that anomalously positive horizontal transport seems to be an inevitable ingredient in the formation of unusually warm temperatures, it does not fully elucidate why certain warm events are more extreme than others. For instance, drier-than-usual soil may be a contributing factor. However, its effect would be clearly reflected in an anomalously strong diabatic heating only if other variables, such as horizontal transport, were not also affecting the diabatic heating. Conditioning on specific factors, such as prescribed dynamics (i.e. prescribed horizontal and vertical transport), might offer a potential avenue to disentangle such effects. Nonetheless, the existing correlations between the respective variables in the decomposition still pose a challenge for drawing causal conclusions.

In summary, our paper suggests that there are at least two different ways to perform a meaningful decomposition of a given temperature anomaly into distinct processes. At the same time, the analysis focused exclusively on the Lagrangian framework; a decomposition in an Eulerian framework would most likely provide yet another perspective. The variety in possible decompositions implies that there is no unique answer regarding the extents to which horizontal transport, vertical transport, and diabatic heating contribute to a given temperature anomaly. Ultimately, the answer to this question seems to be a matter of perspective.

Let τ be the sum of all terms that bring about a change in a parcel's potential temperature anomaly θ′, i.e.

such that

Integrating τ along the parcel's trajectory yields

where t0 is the start time of the integration, t is the time of interest, and is the temperature anomaly at the start time. The integral in Eq. (A3) can be extended to start at −∞ if, at the same time, the part of the integral that arises from the time interval is subtracted:

The latter equation is equivalent to

where we introduced the exponential weighting that allows the application of our tracer method. Defining

and positing that

one obtains

The data presented in this study is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14679142 (Mayer, 2025a). The tracer advection code used to create the data can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14697529 (Mayer, 2025b). The code used to create the plots in this paper is accessible at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14717758 (Mayer, 2025c). All results are based on the ERA5 reanalysis (Hersbach et al., 2017) from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) provided by the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S).

AM carried out the analysis with some advice from VW. Both authors jointly wrote the paper.

The contact author has declared that neither of the authors has any competing interests.

The results contain modified Copernicus Climate Change Service information 2023. Neither the European Commission nor the ECMWF is responsible for any use that may be made of the Copernicus information or data it contains.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We thank the Copernicus Climate Change Service for granting free access to the ERA5 data. Parts of this research were conducted using the supercomputer MOGON 2 and/or advisory services offered by Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (https://hpc.uni-mainz.de, last access: 17 January 2025), which is a member of the AHRP (Alliance for High-Performance Computing in Rhineland Palatinate, https://www.ahrp.info, last access: 17 January 2025) and the Gauss Alliance e.V. The authors gratefully acknowledge the computing time granted on the supercomputer MOGON 2 at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. We made occasional use of ChatGPT to refine sentence structures and improve the formulations of an earlier version of this paper.

This research has been supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant no. SFB/TRR 165).

This open-access publication was funded by Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz.

This paper was edited by Gwendal Rivière and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Barriopedro, D., García-Herrera, R., Ordóñez, C., Miralles, D. G., and Salcedo-Sanz, S.: Heat waves: Physical understanding and scientific challenges, Rev. Geophys., 61, e2022RG000780, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022RG000780, 2023. a

Bieli, M., Pfahl, S., and Wernli, H.: A Lagrangian investigation of hot and cold temperature extremes in Europe: Lagrangian Investigation of Hot and Cold Extremes, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 141, 98–108, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.2339, 2015. a, b, c, d, e

Catalano, A. J., Loikith, P. C., and Neelin, J. D.: Diagnosing Non‐Gaussian Temperature Distribution Tails Using Back‐Trajectory Analysis, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 126, e2020JD033726, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JD033726, 2021. a

Eichner, J. F., Koscielny-Bunde, E., Bunde, A., Havlin, S., and Schellnhuber, H. J.: Power-law persistence and trends in the atmosphere: A detailed study of long temperature records, Phys. Rev. E, 68, 046133, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.68.046133, 2003. a

Garfinkel, C. I. and Harnik, N.: The Non-Gaussianity and Spatial Asymmetry of Temperature Extremes Relative to the Storm Track: The Role of Horizontal Advection, J. Climate, 30, 445–464, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-15-0806.1, 2017. a

Garfinkel, C. I., Rostkier‐Edelstein, D., Morin, E., Hochman, A., Schwartz, C., and Nirel, R.: Precursors of summer heat waves in the Eastern Mediterranean, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 150, qj.4795, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.4795, 2024. a

Harpaz, T., Ziv, B., Saaroni, H., and Beja, E.: Extreme summer temperatures in the East Mediterranean-dynamical analysis, Int. J. Climatol., 34, 849–862, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3727, 2014. a, b, c

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Hirahara, S., Horányi, A., Muñoz‐Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Abdalla, S., Abellan, X., Balsamo, G., Bechtold, P., Biavati, G., Bidlot, J., Bonavita, M., De Chiara, G., Dahlgren, P., Dee, D., Diamantakis, M., Dragani, R., Flemming, J., Forbes, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A., Haimberger, L., Healy, S., Hogan, R. J., Hólm, E., Janisková, M., Keeley, S., Laloyaux, P., Lopez, P., Lupu, C., Radnoti, G., de Rosnay, P., Rozum, I., Vamborg, F., Villaume, S., and Thépaut, J.: Complete ERA5 from 1940: Fifth generation of ECMWF atmospheric reanalyses of the global climate, Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Data Store (CDS) [data set], https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.143582cf, 2017. a

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Hirahara, S., Horányi, A., Muñoz‐Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Abdalla, S., Abellan, X., Balsamo, G., Bechtold, P., Biavati, G., Bidlot, J., Bonavita, M., Chiara, G., Dahlgren, P., Dee, D., Diamantakis, M., Dragani, R., Flemming, J., Forbes, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A., Haimberger, L., Healy, S., Hogan, R. J., Hólm, E., Janisková, M., Keeley, S., Laloyaux, P., Lopez, P., Lupu, C., Radnoti, G., Rosnay, P., Rozum, I., Vamborg, F., Villaume, S., and Thépaut, J.: The ERA5 global reanalysis, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803, 2020. a

Hochman, A., Scher, S., Quinting, J., Pinto, J. G., and Messori, G.: A new view of heat wave dynamics and predictability over the eastern Mediterranean, Earth Syst. Dynam., 12, 133–149, https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-12-133-2021, 2021. a, b

Horton, R. M., Mankin, J. S., Lesk, C., Coffel, E., and Raymond, C.: A Review of Recent Advances in Research on Extreme Heat Events, Current Climate Change Reports, 2, 242–259, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-016-0042-x, 2016. a

Hotz, B., Papritz, L., and Röthlisberger, M.: Understanding the vertical temperature structure of recent record-shattering heatwaves, Weather Clim. Dynam., 5, 323–343, https://doi.org/10.5194/wcd-5-323-2024, 2024. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m

IPCC: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896, 2021. a

Iwasaki, T.: A Diagnostic Formulation for Wave-Mean Flow Interactions and Lagrangian-Mean Circulation with a Hybrid Vertical Coordinate of Pressure and Isentropes, J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn., 67, 293–312, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj1965.67.2_293, 1989. a

Juckes, M.: A generalization of the transformed Eulerian‐mean meridional circulation, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 127, 147–160, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49712757109, 2001. a

Koscielny-Bunde, E., Bunde, A., Havlin, S., Roman, H. E., Goldreich, Y., and Schellnhuber, H.-J.: Indication of a Universal Persistence Law Governing Atmospheric Variability, Phys. Rev. Lett., 81, 729–732, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.81.729, 1998. a

Li, X., Mann, M. E., Wehner, M. F., Rahmstorf, S., Petri, S., Christiansen, S., and Carrillo, J.: Role of atmospheric resonance and land–atmosphere feedbacks as a precursor to the June 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Dome event, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 121, e2315330121, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2315330121, 2024. a

Mayer, A.: Two different perspectives on heatwaves within the Lagrangian framework: Dataset (v1.0), Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14679142, 2025a.

Mayer, A.: The Tracer Method by Mayer and Wirth (v2.1), Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14697529, 2025b.

Mayer, A.: Two different perspectives on heatwaves within the Lagrangian framework: Code for figures, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14717758, 2025c.

Mayer, A. and Wirth, V.: Lagrangian description of the atmospheric flow from Eulerian tracer advection with relaxation, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 149, 1271–1292, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.4453, 2023. a, b, c, d, e

Miralles, D. G., Teuling, A. J., van Heerwaarden, C. C., and Vilà-Guerau de Arellano, J.: Mega-heatwave temperatures due to combined soil desiccation and atmospheric heat accumulation, Nat. Geosci., 7, 345–349, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2141, 2014. a

Neal, E., Huang, C. S. Y., and Nakamura, N.: The 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Wave and Associated Blocking: Meteorology and the Role of an Upstream Cyclone as a Diabatic Source of Wave Activity, Geophys. Res. Lett., 49, e2021GL097699, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL097699, 2022. a, b, c, d

Oertel, A., Pickl, M., Quinting, J. F., Hauser, S., Wandel, J., Magnusson, L., Balmaseda, M., Vitart, F., and Grams, C. M.: Everything Hits at Once: How Remote Rainfall Matters for the Prediction of the 2021 North American Heat Wave, Geophys. Res. Lett., 50, e2022GL100958, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL100958, 2023. a

Papritz, L. and Röthlisberger, M.: A Novel Temperature Anomaly Source Diagnostic: Method and Application to the 2021 Heatwave in the Pacific Northwest, Geophys. Res. Lett., 50, e2023GL105641, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL105641, 2023. a, b

Pelletier, J. D.: Analysis and Modeling of the Natural Variability of Climate, J. Climate, 10, 1331–1342, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1997)010<1331:AAMOTN>2.0.CO;2, 1997. a

Pelletier, J. D. and Turcotte, D. L.: Long-range persistence in climatological and hydrological time series: analysis, modeling and application to drought hazard assessment, J. Hydrol., 203, 198–208, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(97)00102-9, 1997. a

Perkins, S. E.: A review on the scientific understanding of heatwaves – Their measurement, driving mechanisms, and changes at the global scale, Atmos. Res., 164–165, 242–267, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2015.05.014, 2015. a

Pfahl, S. and Wernli, H.: Quantifying the relevance of atmospheric blocking for co-located temperature extremes in the Northern Hemisphere on (sub-)daily time scales, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L12807, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL052261, 2012. a

Philip, S. Y., Kew, S. F., van Oldenborgh, G. J., Anslow, F. S., Seneviratne, S. I., Vautard, R., Coumou, D., Ebi, K. L., Arrighi, J., Singh, R., van Aalst, M., Pereira Marghidan, C., Wehner, M., Yang, W., Li, S., Schumacher, D. L., Hauser, M., Bonnet, R., Luu, L. N., Lehner, F., Gillett, N., Tradowsky, J. S., Vecchi, G. A., Rodell, C., Stull, R. B., Howard, R., and Otto, F. E. L.: Rapid attribution analysis of the extraordinary heat wave on the Pacific coast of the US and Canada in June 2021, Earth Syst. Dynam., 13, 1689–1713, https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-13-1689-2022, 2022. a, b

Quinting, J. F. and Reeder, M. J.: Southeastern Australian Heat Waves from a Trajectory Viewpoint, Mon. Weather Rev., 145, 4109–4125, https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-17-0165.1, 2017. a

Röthlisberger, M. and Papritz, L.: Quantifying the physical processes leading to atmospheric hot extremes at a global scale, Nat. Geosci., 16, 210–216, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-023-01126-1, 2023. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n

Schielicke, L. and Pfahl, S.: European heatwaves in present and future climate simulations: a Lagrangian analysis, Weather Clim. Dynam., 3, 1439–1459, https://doi.org/10.5194/wcd-3-1439-2022, 2022. a, b, c, d

Schumacher, D. L., Keune, J., Van Heerwaarden, C. C., Vilà-Guerau De Arellano, J., Teuling, A. J., and Miralles, D. G.: Amplification of mega-heatwaves through heat torrents fuelled by upwind drought, Nat. Geosci., 12, 712–717, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0431-6, 2019. a

Schumacher, D. L., Hauser, M., and Seneviratne, S. I.: Drivers and Mechanisms of the 2021 Pacific Northwest Heatwave, Earth's Future, 10, e2022EF002967, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF002967, 2022. a, b

Screen, J.: Arctic amplification decreases temperature variance in northern mid- to high- latitudes, Nat. Clim. Change, 4, 577–582, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2268, 2014. a

Sousa, P. M., Trigo, R. M., Barriopedro, D., Soares, P. M. M., and Santos, J. A.: European temperature responses to blocking and ridge regional patterns, Clim. Dynam., 50, 457–477, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3620-2, 2018. a

Sousa, P. M., Barriopedro, D., Ramos, A. M., García-Herrera, R., Espírito-Santo, F., and Trigo, R. M.: Saharan air intrusions as a relevant mechanism for Iberian heatwaves: The record breaking events of August 2018 and June 2019, Weather and Climate Extremes, 26, 100224, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2019.100224, 2019. a

Spensberger, C., Madonna, E., Boettcher, M., Grams, C. M., Papritz, L., Quinting, J. F., Röthlisberger, M., Sprenger, M., and Zschenderlein, P.: Dynamics of concurrent and sequential Central European and Scandinavian heatwaves, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 146, 2998–3013, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3822, 2020. a

Sprenger, M. and Wernli, H.: The LAGRANTO Lagrangian analysis tool – version 2.0, Geosci. Model Dev., 8, 2569–2586, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-8-2569-2015, 2015. a

Stefanon, M., D’Andrea, F., and Drobinski, P.: Heatwave classification over Europe and the Mediterranean region, Environ. Res. Lett., 7, 014023, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/7/1/014023, 2012. a

Stein, A. F., Draxler, R. R., Rolph, G. D., Stunder, B. J. B., Cohen, M. D., and Ngan, F.: NOAA’s HYSPLIT Atmospheric Transport and Dispersion Modeling System, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 96, 2059–2077, 2015. a

Stohl, A.: Computation, accuracy and applications of trajectories – A review and bibliography, Atmos. Environ., 32, 947–966, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(97)00457-3, 1998. a

Stohl, A., Eckhardt, S., Forster, C., James, P., Spichtinger, N., and Seibert, P.: A replacement for simple back trajectory calculations in the interpretation of atmospheric trace substance measurements, Atmos. Environ., 36, 4635–4648, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(02)00416-8, 2002. a

Talkner, P. and Weber, R. O.: Power spectrum and detrended fluctuation analysis: Application to daily temperatures, Phys. Rev. E, 62, 150–160, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.62.150, 2000. a

Townsend, R. D. and Johnson, D. R.: A diagnostic study of the isentropic zonally averaged mass circulation during the first GARP global experiment, J. Atmos. Sci., 42, 1565–1579, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1985)042<1565:ADSOTI>2.0.CO;2, 1985. a

White, R. H., Anderson, S., Booth, J. F., Braich, G., Draeger, C., Fei, C., Harley, C. D. G., Henderson, S. B., Jakob, M., Lau, C.-A., Mareshet Admasu, L., Narinesingh, V., Rodell, C., Roocroft, E., Weinberger, K. R., and West, G.: The unprecedented Pacific Northwest heatwave of June 2021, Nat. Commun., 14, 727, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36289-3, 2023. a, b

Zschenderlein, P., Fink, A. H., Pfahl, S., and Wernli, H.: Processes determining heat waves across different European climates, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 145, 2973–2989, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3599, 2019. a, b, c, d, e