the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Mediterranean Sea heat uptake variability as a precursor to winter precipitation in the Levant

Ofer Cohen

Assaf Hochman

Ehud Strobach

Dorita Rostkier-Edelstein

Hezi Gildor

The Eastern Mediterranean is experiencing severe warming and drying, driven by global warming, making seasonal precipitation prediction in the region imperative. Given that the Mediterranean Sea is the primary source of regional moisture and synoptic variability, here we explore the observed relation of Mediterranean Sea variability to Levant land precipitation during winter – the dominant wet season. Using Empirical Orthogonal Function (EOF) objective analysis, we identify three dominant modes of sea surface temperature (SST) and ocean heat uptake variability in the Mediterranean Sea. Of these, two modes characterized by east-west variations are found to be statistically related to winter land precipitation in the Levant. Based on these relations, we define an Aegean Sea heat uptake anomaly index (AQA), which is strongly correlated with Levant winter precipitation. Specifically, AQA values during August are found to predict Levant land precipitation in the following winter (December–February, ). Wetter winters over the Levant following negative August AQA values are associated with more persistent eastward-propagating Mediterranean storms, driven by enhanced baroclinicity and a stronger subtropical jet. The results present AQA as a useful seasonal predictor of Levant winter precipitation and indicate that representations of processes affecting Mediterranean cyclones, the subtropical jet, and ocean-atmosphere heat exchange are key to seasonal forecasting skill in the Levant.

- Article

(7399 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(5569 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The Eastern Mediterranean (EM) is generally recognized as a global warming “hotspot”, projected to experience significant climatic changes, including rising temperatures and intensified droughts, as well as extreme precipitation events and flooding (Giorgi, 2006; Lionello et al., 2006; Lelieveld et al., 2012; Cramer et al., 2018; Zittis et al., 2022; Hochman et al., 2022a, 2021b, 2018d; Samuels et al., 2018). Seasonal precipitation prediction in the Levant, a region prone to water stress, is therefore crucial for adaptation efforts. Given that the Mediterranean Sea is a critical source of moisture and a key driver of synoptic variability influencing precipitation in the Levant, we investigate the observed impact of spatiotemporal variability in the Mediterranean Sea on winter precipitation in the Levant.

The EM lies in a transitional climate zone, subtended by temperate regions to the north and arid regions to the south (Goldreich, 2003; Ziv et al., 2006). EM climate is marked by relatively dry summers and wet winters, with the majority of precipitation occurring from December to February (Fig. 1a). Seasonal synoptic patterns in the region result from the interaction of large-scale systems, such as the subtropical jet, subtropical highs, and the Asian monsoon, with smaller regional systems, and are modulated by the conditions in the Mediterranean Sea (Eshel and Farrell, 2000; Goldreich, 2003; Alpert et al., 2004b; Ziv et al., 2006; Lionello et al., 2006; Saaroni et al., 2010; Hochman et al., 2022b). The interaction of global and regional systems, therefore, critically affects precipitation predictability in the region (Baruch et al., 2006; Hochman et al., 2018a, 2023).

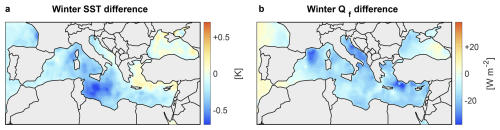

Figure 1(a) Winter (December–February) minus summer (June–August) precipitation in the Mediterranean region; a black rectangle demarcates the Levant region considered in this study. (b) Pearson correlation coefficient of winter land precipitation in the Levant region and global sea surface temperature (SST) in the preceding September, for the period 1979–2023 (correlation 95 % confidence bounds are shown in gray contours). Data taken from the ERA5 reanalysis (Hersbach et al., 2020, see Sect. 2.1).

Various indices based on surface and atmospheric conditions in the Mediterranean have been used to capture precipitation and temperature variations in the Mediterranean basin (Conte et al., 1989; Palutikof, 2003; Martin-Vide and Lopez-Bustins, 2006; Criado-Aldeanueva and Soto-Navarro, 2013; Redolat et al., 2019). In particular, multiple versions of a Mediterranean Oscillation index have been examined, motivated by the characteristic atmospheric east-west dipole in the Mediterranean basin (Conte et al., 1989). These, however, have shown limited predictive value in the EM on seasonal timescales (Redolat et al., 2019). In contrast, statistical approaches incorporating delayed interactions and ocean-atmosphere heat fluxes have shown significant potential for improving seasonal forecasting in the EM (Redolat and Monjo, 2024).

Recent work has demonstrated a delayed response of Levant precipitation to large-scale variations, which can serve as a basis for improved predictions of seasonal precipitation in the region (Amitai and Gildor, 2017; Hochman et al., 2022b, 2024). For example, statistical relations were established between Mediterranean Sea heat content in autumn and subsequent winter precipitation in several cities across Israel (Tzvetkov and Assaf, 1982; Amitai and Gildor, 2017). Synoptic weather systems in the EM were also shown to be modulated by the Mediterranean Sea, with Mediterranean SST changes affecting the development and intensity of Mediterranean cyclones, thereby delaying inland winter precipitation peaks from early to late January compared to coastal regions (Ziv et al., 2006; Flaounas et al., 2018). Such variations in sea surface conditions are expected to have both dynamic and thermodynamic impacts on EM precipitation, influencing both atmospheric flow and regional synoptic conditions, as well as the thermodynamic properties of advected air parcels (Seager et al., 2014; Elbaum et al., 2022; Tootoonchi et al., 2025; Seager et al., 2024).

Despite the Mediterranean's importance for Levant winter precipitation, previous work has primarily focused on remote links known to influence conditions in the EM. For example, Fig. 1b shows a global lagged correlation map of observed SST anomalies in September and winter Levant land precipitation. Significant lagged correlations are seen in various regions, including the tropical Pacific, the North Atlantic, and the Indian Ocean. The positive lagged correlation in the North Atlantic agrees with previous works showing links between positive phases of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and Arctic Oscillation (AO) and winter precipitation in the Levant, mediated by the effect of NAO and AO on the intensity of winter storms in the EM (Eshel and Farrell, 2000; Black, 2012; Givati and Rosenfeld, 2013; Luo et al., 2015), as well as upstream amplification of extratropical cyclones originating in the North Atlantic (Raveh-Rubin and Flaounas, 2017). The lagged correlations in the Tropical Pacific are consistent with previous work linking ENSO and winter precipitation in northern Israel during the second half of the 20th century (Price et al., 1998). Similarly, SST variability in the Indian and Pacific Oceans is dynamically linked to sub-seasonal precipitation variability in the Levant (Hochman et al., 2024; Hochman and Gildor, 2025; Reale et al., 2025).

Significant lagged correlations are also seen in the Mediterranean Sea, which are the focus of the present analysis. In particular, the lagged spatial correlation patterns in the Mediterranean Sea vary across months (not shown), suggesting non-trivial regional links between Levant precipitation and Mediterranean Sea variability, which are explored here. Specifically, we aim to: (i) explore the observed links between objectively determined patterns of variability in the Mediterranean Sea and Levant winter precipitation; and (ii) analyze the physical processes underlying these links. Our results point to key variations in the Mediterranean Sea that precede Levant winter precipitation anomalies, potentially providing a basis for improved seasonal prediction.

Our methodology is based on calculating the observed dominant spatiotemporal patterns of surface heat balance variability in the Mediterranean Sea using objective methods, and identifying which elements of these modes of variability hold predictive power for Levant precipitation. This is then followed by an analysis of the regional moisture balance (Seager et al., 2010, 2014) and synoptic conditions (Alpert et al., 2004b), providing context for the lagged response of Levant precipitation to Mediterranean Sea variability. The data, ocean mixed-layer heat balance, objective analysis methods, and analyses of moisture balance and synoptic conditions are briefly described below.

2.1 Data

For atmospheric and surface data, we use monthly and daily data from the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5 atmospheric reanalysis at 0.25° × 0.25° grid-spacing, covering the period 1979–2023 (i.e., post-satellite era; Hersbach et al., 2020). ERA5 data has been shown in previous studies to provide reliable estimates of in situ observations of the hydrological cycle (Seager et al., 2024; Tootoonchi et al., 2025). We nevertheless validate our results using in situ data from rain gauges distributed throughout Israel provided by the Israel Meteorological Service (IMS, https://ims.gov.il, last access: 7 January 2025). In accordance with ERA5, the reference observed sea surface temperature (SST) data are taken from the HadISST2 dataset (Titchner and Rayner, 2014) up to September 2007 and from the Operational SST and Ice Analysis (OSTIA) dataset (Good, 2022) thereafter. For precipitation over land, we use ERA5-land (Muñoz-Sabater et al., 2021) at approximately 9 km resolution, which provides an improved representation of land processes.

2.2 Ocean mixed-layer energy balance

Upper-ocean heat content, given by the product of sea-water heat capacity cp, ocean mixed-layer depth (hml, MLD), and SST (T), has been shown in previous work to be a contributing factor to processes affecting Levant precipitation over land, such as ocean-atmosphere heat and moisture exchange and land-ocean temperature contrasts (Amitai and Gildor, 2017; Tzvetkov and Assaf, 1982). In particular, Tzvetkov and Assaf (1982) and Amitai and Gildor (2017) demonstrated the potential of utilizing the ocean's upper-layer heat content during fall months to enhance predictions of winter precipitation in the Levant. Building on these results, we hypothesize that changes in Mediterranean SST and ocean heat uptake are linked to precipitation changes in the Levant. However, since estimates of MLD can vary significantly across datasets and methodologies (Kara et al., 2000; d'Ortenzio et al., 2005; Treguier et al., 2023; Keller et al., 2024), we avoid using MLD as a predictor.

Specifically, the energy balance equation of the ocean mixed layer can be written as (Gill, 1982)

where is SST tendency, is the vertical-mean horizontal flow in the mixed layer, Qf is the net downward heat flux at the ocean surface, and Kz is the input of heat to the mixed layer from below, associated primarily with small-scale vertical mixing. Here positive Qf values indicate heating of the upper ocean and negative Qf values indicate release of heat from the ocean surface to the atmosphere. Also, for sufficiently small temporal variations of the ocean mixed layer depth, SST tendency is approximately proportional to Qf.

The net surface energy input into the ocean mixed layer (Qf) consists of the net downward shortwave (SW) and longwave (LW) surface radiation, and the downward sensible (SH) and latent (LH) surface heat fluxes, minus the fraction of the shortwave radiation penetrating below the mixed layer (QP)

where QP is calculated as a 25-m e folding decay of shortwave radiation, given by the equation QP=0.45 SW , with γ being a decay rate constant equal to 0.04 m−1 (Wang and McPhaden, 1999; Vallès-Casanova et al., 2025).

2.3 Empirical Orthogonal Function (EOF) Analysis

To objectively capture the spatial patterns of Mediterranean Sea variability, we employ the Empirical Orthogonal Function (EOF) analysis (Hannachi et al., 2007), as well as Self-Organizing Map (SOM) unsupervised neural network analysis for clustering and visualizing high-dimensional data (Kohonen, 1990). The two methods yield very similar spatial patterns and temporal behavior. We therefore focus in our analysis on the EOF patterns, but provide additional results for the SOM analysis in the Supplement (Sect. S1).

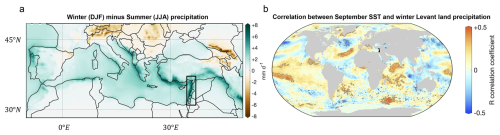

We produce EOF patterns of SST and ocean heat uptake (Qf) in the Mediterranean Sea, using detrended monthly anomalies from climatology. The EOFs are computed as the eigenvectors of the covariance matrices of SST and Qf, representing the primary orthogonal modes of variability in the SST and Qf data. The variance explained by each EOF mode is calculated as each eigenvalue of the covariance matrix of SST and Qf normalized by the sum of all eigenvalues. The corresponding time series of the relative amplitude of each EOF pattern (the principal component) is used to quantify how the dominance of these patterns varies over time. Subsequently, we calculate the lagged Pearson correlation coefficient between the monthly amplitude of each pattern and winter (December–February) mean land precipitation in the Levant (Fig. 2).

Figure 2The first three EOF patterns of Mediterranean monthly (a–c) SST and (e–g) heat uptake (Qf) anomalies. The variance explained (VE) by each pattern is shown in the panel titles. (d, h) Lagged correlation of the principal component of each monthly SST and Qf EOF pattern, respectively, during the months July–November with mean Levant winter (DJF) land precipitation. Statistically significant (5 % significance level) correlations are bolded. Data taken from ERA5 for 1979–2023 (Hersbach et al., 2020).

2.4 Decomposition of precipitation variations

The steady moisture equation of the atmosphere can be written as (Seager et al., 2010)

where P and E represent precipitation and evaporation, respectively, u is the wind vector, q denotes specific humidity, p denotes pressure, and the subscript (⋅)s denotes surface values. Angled brackets denote mass-weighted vertical integrals,

where ρw is the density of water and g is Earth's gravitational acceleration; overbars and primes denote monthly temporal means and deviations thereof, respectively.

Following the methodology and terminology described in Seager et al. (2010), it follows from Eq. (3) that changes in precipitation can be decomposed into those involving changes in evaporation, the mean wind field (dynamic changes), the mean moisture field (thermodynamic changes), surface moisture transport, and transient eddies (Seager et al., 2010, 2014; Kaspi and Schneider, 2013; Wills et al., 2016; Elbaum et al., 2022; Tootoonchi et al., 2025; Bril et al., 2025).

We define δ as the difference between two composites of monthly means,

where a double overbar denotes a temporal average over some period. Neglecting changes associated with surface pressure, we rewrite the moisture balance equation to express the difference between two composites of winters,

In the next section, we refer to the second and third right-hand side terms as the changes in the mean and transient components of precipitation, respectively, where the mean component is further decomposed into mean thermodynamic () and the mean dynamic () components (Seager et al., 2010).

2.5 Semi-Objective Synoptic Classification

Due to the critical influence of synoptic-scale conditions on precipitation in the Levant (Lionello et al., 2006; Goldreich, 2003), we examine the relationship between these conditions and our calculated patterns of variability. Specifically, we classify synoptic conditions based on the semi-objective methodology proposed by Alpert et al. (2004b), which has been used in previous works to study EM seasonal synoptic variations (Alpert et al., 2004a), as well as changes under climate change in weather patterns (Hochman et al., 2018c, b, 2020; Ludwig and Hochman, 2022), extreme weather events (Rostkier-Edelstein et al., 2016; Hochman et al., 2022a), and their impacts (Hochman et al., 2021a).

The classification method uses four single-level atmospheric fields: geopotential height, temperature, and the zonal and meridional components of wind; all at 1000 hPa and at a grid-spacing of 2.5° × 2.5° over the EM region (defined within the coordinates 27.5–37.5° N and 30–40° E), sampled at 12:00 UTC each day. The synoptic classification of each day within the EM is therefore calculated using 100 data points (5×5 grid points for each of the four atmospheric fields), which are also standardized by subtracting the long-term mean and dividing by the standard deviation of the time series of each field. The classification of each day to its synoptic type is performed by comparing each of these daily datasets to 426 d that were manually classified by a team of expert meteorologists (335 d from 1985 and 91 d from the winter of 1991–1992). The synoptic type of each day is determined as that for which the Euclidean distance from each of the manually classified days is lowest. The reference 426 d are categorized into five synoptic groups (Alpert et al., 2004b), of which two are associated with winter precipitation:

- i.

Cyprus Low (CL): A Mediterranean cyclone centered near Cyprus, often responsible for significant rainfall and stormy weather in the Levant region and significant impacts (Khodayar et al., 2025; Hochman et al., 2021a);

- ii.

Red Sea Trough (RST): A low-pressure trough extending from the southern Red Sea into the EM, often associated with warm, moist air advection and convective activity. It produces occasional intense precipitation during transition seasons in the southeastern Levant.

The remaining three synoptic groups are associated with warm and dry conditions:

- iii.

Highs (H): A high-pressure system over the EM throughout the year (as an extension of the Siberian high), leading to stable, dry, and clear weather;

- iv.

Persian Trough (PT): A thermal low originating over the Persian Gulf and extending westward, typically bringing warm and moist conditions to the EM during summer;

- v.

Sharav Low (SL): A transient heat low forming over the western Sahara and moving eastward, bringing hot, dry, and windy conditions to the EM, typically during spring.

To better identify the driving factors impacting the synoptic change, we analyze the regional atmospheric conditions between winter composites. Accordingly, we study the changes in mean sea-level pressure conditions, the 500 hPa geopotential, and the strength and position of the subtropical jet. Additionally, to quantify the difference in the regional baroclinic conditions, we use the Eady Growth Rate, as defined in Hoskins and Valdes (1990):

Where σ is the Eady Growth Rate between the 850 and 500 hPa pressure levels, f is the Coriolis parameter, N is the Brunt-Väisälä frequency, and ∂zv) is the vertical shear of the horizontal wind.

We begin by calculating the spatiotemporal patterns of variability in Mediterranean SST and surface heat uptake (Qf). Based on these patterns, we define an index that captures a strong statistical relation between summer Qf anomalies in the Aegean Sea and winter precipitation anomalies in the Levant (December–January average over land). We then provide context for this relation using analyses of the regional hydrological cycle and synoptic conditions.

3.1 Spatiotemporal patterns of variability

For both SST and Qf, the first three EOF patterns explain the majority of the variance in the data (76 % for SST and 78 % for Qf, left and right columns of Fig. 2, respectively), indicating they represent the dominant patterns of variability in these fields. The first EOF pattern (Fig. 2a, e, 47 % variance explained in both fields) can be described as generally capturing a gradient between the central Mediterranean and its eastern and western parts. The second EOF pattern of SST and Qf (Fig. 2b, f, 24 % and 27 % variance explained, respectively) generally captures east-west gradients across the Mediterranean basin, consistent with the characteristic east-west dipole seen in atmospheric variables (Conte et al., 1989). Specifically, the second EOF pattern of SST and Qf alike features a surface anomaly located between the Ionian and Tyrrhenian Seas (i.e., east and west of Sicily). The third EOF pattern of SST and Qf explains 5 % and 4 % of the variance, respectively, and depicts a north-south gradient of SST and Qf anomalies over the Mediterranean.

Statistically significant lagged correlations of the principal components of the EOF patterns and Levant winter precipitation are seen in different months for the three EOFs (Fig. 2d, h). Of these, the second EOF pattern of Qf stands out with a correlation coefficient in August and R=0.40 in October. During the peak correlation month of August, Qf variations are dominated by latent heat fluxes, with minor contributions from sensible heat fluxes and negligible contributions from radiative fluxes (Fig. S15). Since latent and sensible heat fluxes are strongly dependent on near-surface winds and atmospheric conditions (i.e., temperature and humidity), this suggests that coupled ocean-atmosphere processes are linked to the lagged correlations.

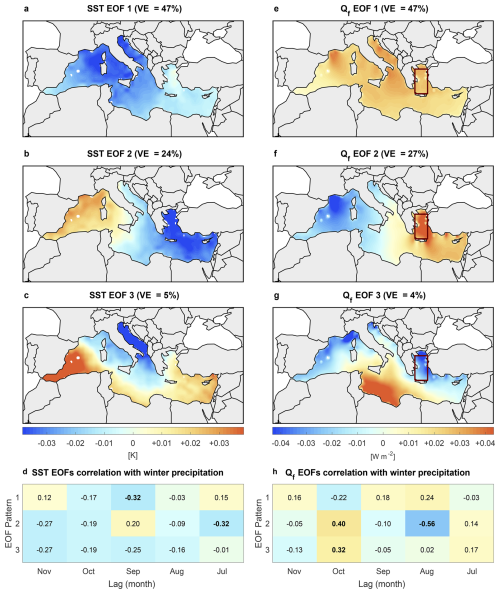

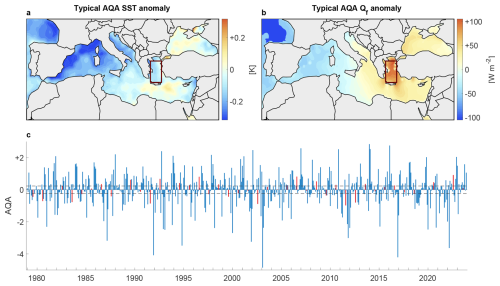

Figure 3Aegean Qf anomaly Index (AQA), defined as the detrended anomaly from climatology of Qf in the Aegean Sea (23.5–26.5° E, 32.5–35° N, red rectangles in panels a and b), normalized by the standard deviation of the anomaly timeseries. The typical difference between (a) SST and (b) Qf positive and negative AQA months (taken as months above or below ±0.5 the standard deviation of AQA). (c) Monthly AQA values from January 1979 to December 2023. August months, which are the most strongly correlated with winter Levant land precipitation, are shown in red. Gray dashed horizontal lines denote ±0.5 the standard deviation of August AQA values.

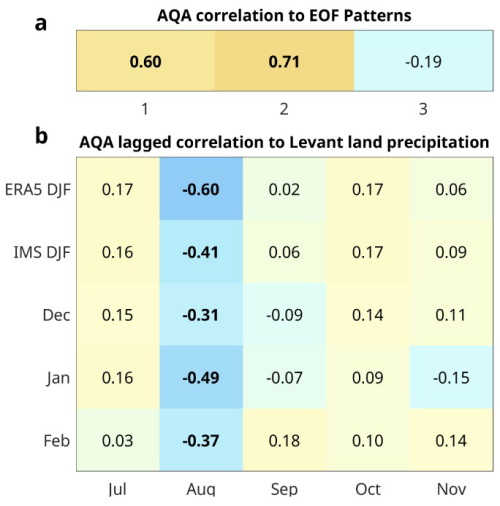

Figure 4(a) Correlations of the Aegean Qf anomaly index (AQA) with the Qf EOF patterns. (b) Correlations of AQA with Levant land winter precipitation using ERA5-land data and rain gauge data from the Israel Meteorological Service (IMS, https://ims.gov.il, last access: 7 January 2025). The p-values and 95 % upper and lower bounds of the AQA correlations to Levant land precipitation anomalies are shown in Fig. S17.

3.2 Aegean Qf Anomaly index

We find that mean Qf values in the Aegean Sea reproduce the lagged correlations with Levant precipitation seen for the second EOF pattern. We therefore define an Aegean Sea Qf Anomaly index (AQA) as a precursor to Levant winter land precipitation. Specifically, AQA is defined as the Qf detrended anomaly from seasonal climatology in the north-eastern region demarcated in Fig. 3a–b (23.5–26.5° E, 32.5–35° N), normalized by the standard deviation of the anomaly timeseries. Note, however, that based on the second Qf EOF pattern, this index does not only indicate Qf changes in the Aegean Sea, but also contrasting Qf changes in the western Mediterranean (and similarly for SST; Fig. 2). The AQA index was found to have considerably stronger predictive power compared to indices based on other regions of the Mediterranean and is not sensitive to ±0.25° variations of its boundaries (Fig. S11). A similar AQA index based on SST yields similar but statistically weaker results (see Sect. S2).

Monthly AQA values are shown in Fig. 3c. AQA is unitless, with positive values indicating higher ocean heat uptake in the Aegean Sea relative to climatological conditions (Fig. 3a, b). AQA is strongly anti-correlated with the principal component of the first and second Qf EOF patterns (R=0.60 and R=0.71 respectively, Fig. 4a) and can therefore be interpreted as generally proportional to the amplitude of these EOF patterns.

AQA is significantly correlated with Levant winter precipitation, in both ERA5 data and in situ IMS rain gauges, with the strongest lagged correlation in August (), in agreement with the Qf Patterns 2 and 3 (Fig. 4a). The correlation is strongest for winter (December–February), but is significant for each of the winter months (Fig. 4b). These results are not sensitive to the choice of December–February as the winter months, and remain significant for earlier, later, or longer winter months combinations (specifically, November–March, November–January, and January–March, shown in Fig. S9).

We now turn to analyzing the winter conditions associated with AQA variations by examining the differences between composites of winters preceded by August AQA values below and above plus and minus half of the standard deviation of August AQA values (∼13 years in each composite group; cf. Fig. 3). The difference in winter SST between the two composites, shown in Fig. 5a, exhibits higher SST conditions in the north-eastern Mediterranean, which persist throughout winter (not shown). The increased winter SST in the north-eastern Mediterranean is indicative of increased upward surface heat and moisture fluxes, which, in turn, imply favorable conditions for cyclogenesis and storm intensification (e.g., Flaounas et al., 2022). Accordingly, the winter Qf difference between these winter composites (Fig. 5b) shows decreased ocean heat uptake in the EM, driven primarily by increased upward latent and sensible heat fluxes during negative AQA composite winters.

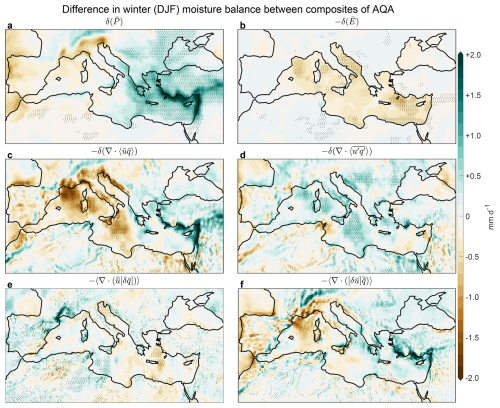

The composite difference of hydrological changes is shown in Fig. 6. A significant increase in precipitation is seen in the EM (Fig. 6a). The majority of the precipitation increase is seen in the mean component of the moisture flux convergence (Fig. 6c), with minor contribution from transient eddies in the northern Levant (Fig. 6d), and negligible contribution from changes in evaporation (Fig. 6b). Further decomposition of the mean component (Fig. 6c) shows that the mean thermodynamic component (Fig. 6e) is negligible, while the mean dynamic component dominates the precipitation response (Fig. 6f).

We therefore conclude that the increased winter Levant precipitation associated with negative AQA anomalies during the preceding August is mediated by changes in regional mean flow patterns, creating more favorable conditions for precipitation by synoptic systems migrating eastward from the central Mediterranean to the Levant. Next, we turn to synoptic analysis to diagnose the meteorological conditions underlying the winter precipitation response to AQA.

Figure 6The decomposed hydrological balance in the Mediterranean region. Bars denote monthly means, and primes denote transient variations. Dotted regions are 95 % statistically significant using a bootstrapping test. (a) Changes in precipitation between negative and positive AQA index winter composites, respectively; (b) Changes in evaporation between composites; (c) Changes in the mean vertically integrated moisture balance; (d) Changes in the transient-eddy component of the moisture flux; (e) Changes in the mean thermodynamic component; (f) Changes in the mean dynamic component.

3.3 Synoptic analysis

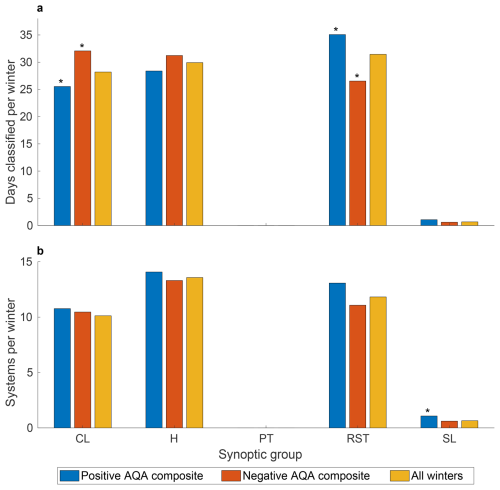

Using the semi-objective synoptic classification (Alpert et al., 2004b), we assess the difference in synoptic conditions between winters preceded by August AQA values above and below half the standard deviation of August AQA values (Fig. 7a). Negative August AQA values are associated with increased prevalence of Cyprus Lows (CL, 32 vs. 25 d per winter) and decreased prevalence of Red Sea Trough systems (RST, 27 vs. 35 d per winter), with negligible changes in the other synoptic groups. Given that winter precipitation in the EM is dominated by eastward propagating Mediterranean cyclones (i.e., Cyprus Lows; Saaroni et al., 2010), and that Red Sea Trough synoptic conditions rarely lead to precipitation, these results are consistent with the winter precipitation response to AQA shown in Fig. 6a.

To assess whether the enhanced Cyprus Low activity results from increased number or duration of storms, we calculate the composite difference in the number of synoptic systems occurring in the region during winter (defined as the number of days minus the number of consecutive days of each synoptic type during winter; Fig. 7b). The number of Cyprus Low systems, as well as of Red Sea Trough and High systems, shows no significant sensitivity to AQA. This, in turn, indicates that the wetter Levant winters in response to negative AQA anomalies in the preceding August result from more persistent precipitating Cyprus Low systems during winter.

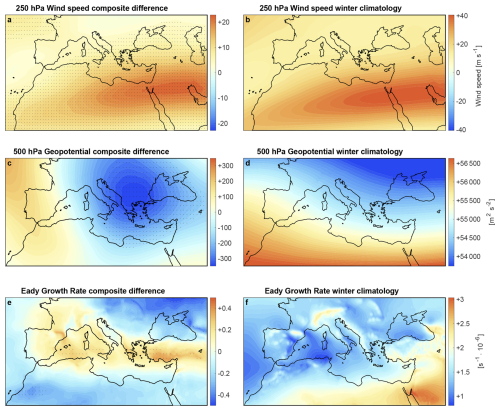

Since the hydrological decomposition pointed to changes in the mean flow as the primary driver of wetter Levant winters (Fig. 6f), we now asses the relation of AQA to the prevailing regional westerlies. As shown in Fig. 8a, negative AQA values in August are associated with a stronger subtropical jet over the EM during winter, which goes along with a low sea-level pressure anomaly over the Aegean Sea (Fig. S4) and a negative 500 hPa geopotential anomaly north of the Aegean Sea (Fig. 8c). This large-scale jet intensification coincides with increased upper-level divergence along EM storm tracks (Fig. S5) and a positive anomaly in the Eady Growth Rate (Fig. 8e), both indicative of more favorable conditions for baroclinic convective instability, consistent with the increased precipitation in the Levant (Fig. 6a).

In summary, our findings reveal that a negative ocean heat uptake anomaly in the Aegean Sea during August is a precursor to enhanced winter precipitation in the Levant. This link is dynamically mediated by the increased persistence of precipitating Cyprus Low systems traversing the region, driven by a strengthening of the subtropical jet over the EM and a concurrent intensification of regional baroclinicity.

Figure 7(a) The number of winter days classified as each synoptic group, and (b) the number of winter synoptic systems, for composites of all winters (yellow bars), and winters preceded by August AQA values above (blue bars) and below (red bars) plus and minus half of the standard deviation of August AQA values. Asterisks denote that the change is significantly different above the 90 % threshold using the binomial significance test.

Figure 8Composite difference between winters (December–February) preceded by negative and positive August AQA values in (a) 250 hPa wind during winter, (c) geopotential height at the 500 hPa pressure level, and (e) Eady Growth Rate. Right column panels show the respective winter climatology. Data taken from ERA5 for 1979–2023. Stippling indicates 95 % confidence estimated using a bootstrap test.

The relation of Mediterranean Sea variability and winter precipitation in the Levant is explored. Objective analysis reveals that changes in the Mediterranean Sea heat uptake act as a precursor to inter-annual variability in Levantine winter precipitation. Based on this, we define an Aegean Sea heat uptake anomaly index (AQA), representing anomalous ocean heat uptake (Qf) in the Aegean Sea during August. AQA shows a significant negative correlation with subsequent winter land precipitation in the Levant (). The associated increase in precipitation is driven by the more persistent eastward-migrating Mediterranean storms, which constitute the dominant source of winter rainfall in the region. This increase is linked to a strengthening of the regional subtropical jet, promoting enhanced baroclinicity and more favorable conditions for storm development and maintenance.

Specifically, using Empirical Orthogonal Functions (EOF) analysis, we identify three dominant spatiotemporal patterns of variability in Mediterranean SST and Qf (Fig. 2). Of these, the patterns characterized by east-west gradients are found to predict variations in Levant winter precipitation. The statistical relations are significant for both SST and Qf, and are qualitatively reproduced for in situ data in Israel. Similar patterns of variability and lagged correlations are produced with Self-Organizing maps (SOM) analysis (Sect. S1), indicating that the results are not sensitive to our methodology. The Qf anomalies, which are generally anti-correlated with SST anomalies (Fig. 3), are primarily driven by changes in latent heat fluxes (Hochman et al., 2022b), highlighting the important role of ocean-atmosphere interactions in Mediterranean Sea variability, and in particular in the lagged response of Levant precipitation.

Composite analysis of winters preceded by negative August AQA values reveals a response characterized by:

- i.

Enhanced precipitation in the Eastern Mediterranean (EM), particularly in the Levant and southern Turkey (Fig. 6);

- ii.

Elevated SST in the northern parts of the EM, a low-pressure region centered north of the Aegean Sea (Figs. S4 and 8c), and reduced Qf throughout the EM (Fig. 5);

- iii.

More persistent eastward migrating EM Mediterranean cyclones, commonly termed Cyprus Lows (Fig. 7a);

- iv.

Strengthened regional subtropical jet, which goes along with more baroclinic conditions in the EM, and enhanced upper-level divergence (Figs. 8 and S5).

A decomposition of the winter regional moisture balance indicates that the wetter Levant winters following negative August AQA values are associated with changes in the mean flow (Fig. 6), in agreement with the observed strengthening of the regional jet and the associated baroclinic instability inducing wetter winters. The strengthening of the subtropical jet is consistent with geostrophic enhancement (i.e., increasing horizontal pressure gradients with height) by the low north of the Aegean Sea. However, additional confounding factors such as interaction with the polar jet and eddy heat and momentum fluxes may also play a role (Flaounas et al., 2022). Furthermore, the physical mechanisms underlying the lagged atmospheric response to sea surface conditions remain unclear, and may require further analysis of Mediterranean Sea dynamics, which have not been examined here. Given that remote regions are known to affect Levant precipitation (Fig. 1), the relation of AQA and Levant precipitation may be mediated by contributing factors outside the Mediterranean basin. However, we find no appreciable statistical relations between AQA and indices known to be related to Levant precipitation, such as the North Atlantic Oscillation index (NAO), the Southern Oscillation index (SOI), and the SST anomaly in the NINO 3.4 region in the Pacific (Figs. 1 and S3; Price et al., 1998; Black, 2012; Givati and Rosenfeld, 2013; Luo et al., 2015). Nevertheless, an indirect relation of Mediterranean Sea variability to remote regions cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor to the lagged response.

AQA, therefore, emerges as a potentially useful index for improving the skill of seasonal precipitation forecasts in the Levant, accounting for approximately one-third of inter-annual variability. In addition, the mechanisms linking AQA and Levant precipitation suggest that the representation in regional models of processes affecting Mediterranean cyclones, ocean-atmosphere heat exchange, and the subtropical jet, is key for improving seasonal forecasts (Flaounas et al., 2022, 2025; Redolat and Monjo, 2024). We intend to isolate the processes contributing to the lagged response and assess their influence on seasonal forecast skill in future work.

The data presented here is available via the ECMWF Data Store and via the IMS website (https://ims.gov.il, last access: 7 January 2025). Code used in the analysis presented here can be obtained upon request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/wcd-7-263-2026-supplement.

Data analysis and writing were done by OC. OA and AH contributed to the conceptual derivation of the methodology and results. All other co-authors provided editorial contributions.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The research was funded by Grant 4749 of the Israeli Ministry of Innovation, Science, and Technology. AH acknowledges support by the Israel Science Foundation (grant #978/23), the Nuclear Research Center of Israel, and the Planning and Budgeting Committee of the Israeli Council for Higher Education under the `Med World’ Consortium.

This research has been supported by the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Technology (grant no. 4749) and the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 978/23).

This paper was edited by Silvio Davolio and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Alpert, P., Osetinsky, I., Ziv, B., and Shafir, H.: A new seasons definition based on classified daily synoptic systems: an example for the eastern Mediterranean, International Journal of Climatology: A Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 24, 1013–1021, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1037, 2004a. a

Alpert, P., Osetinsky, I., Ziv, B., and Shafir, H.: Semi-objective classification for daily synoptic systems: Application to the eastern Mediterranean climate change, International Journal of Climatology: A Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 24, 1001–1011, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1036, 2004b. a, b, c, d, e

Amitai, Y. and Gildor, H.: Can precipitation over Israel be predicted from Eastern Mediterranean heat content?, International Journal of Climatology, 37, 2492–2501, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.4860, 2017. a, b, c, d

Baruch, Z., Dayan, U., Kushnir, Y., Roth, C., and Enzel, Y.: Regional and global atmospheric patterns governing rainfall in the southern Levant, Int. J. Climatol, 26, 55–73, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1238, 2006. a

Black, E.: The influence of the North Atlantic Oscillation and European circulation regimes on the daily to interannual variability of winter precipitation in Israel, International Journal of Climatology, 32, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.2383, 2012. a, b

Bril, E., Torfstein, A., Yaniv, R., and Hochman, A.: Hydroclimatic Variability and Weather-Type Characteristics in the Levant During the Last Interglacial, EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2025-3088, 2025. a

Conte, M., Giuffrida, S., and Tedesco, S.: The Mediterranean oscillation: impact on precipitation and hydrology in Italy. In Proceedings of the Conference on Climate and Water, Vol. 1., Publications of Academy of Finland: Helsinki, 121–137, 1989. a, b, c

Cramer, W., Guiot, J., Fader, M., Garrabou, J., Gattuso, J.-P., Iglesias, A., Lange, M. A., Lionello, P., Llasat, M. C., Paz, S., Peñuelas, J., Snoussi, M., Toreti, A., Tsimplis, M. N., and Xoplaki, E.: Climate change and interconnected risks to sustainable development in the Mediterranean, Nature Climate Change, 8, 972–980, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0299-2, 2018. a

Criado-Aldeanueva, F. and Soto-Navarro, F. J.: The mediterranean oscillation teleconnection index: station-based versus principal component paradigms, Advances in Meteorology, 2013, 738501, https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/738501, 2013. a

d'Ortenzio, F., Iudicone, D., de Boyer Montegut, C., Testor, P., Antoine, D., Marullo, S., Santoleri, R., and Madec, G.: Seasonal variability of the mixed layer depth in the Mediterranean Sea as derived from in situ profiles, Geophysical Research Letters, 32, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005gl022463, 2005. a

Elbaum, E., Garfinkel, C. I., Adam, O., Morin, E., Rostkier-Edelstein, D., and Dayan, U.: Uncertainty in projected changes in precipitation minus evaporation: Dominant role of dynamic circulation changes and weak role for thermodynamic changes, Geophysical Research Letters, 49, e2022GL097725, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL097725, 2022. a, b

Eshel, G. and Farrell, B. F.: Mechanisms of eastern Mediterranean rainfall variability, Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 57, 3219–3232, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(2000)057<3219:moemrv>2.0.co;2, 2000. a, b

Flaounas, E., Kelemen, F. D., Wernli, H., Gaertner, M. A., Reale, M., Sanchez-Gomez, E., Lionello, P., Calmanti, S., Podrascanin, Z., Somot, S., Akhtar, N., Romera, R., and Conte, D.: Assessment of an ensemble of ocean–atmosphere coupled and uncoupled regional climate models to reproduce the climatology of Mediterranean cyclones, Climate Dynamics, 51, 1023–1040, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-016-3398-7, 2018. a

Flaounas, E., Davolio, S., Raveh-Rubin, S., Pantillon, F., Miglietta, M. M., Gaertner, M. A., Hatzaki, M., Homar, V., Khodayar, S., Korres, G., Kotroni, V., Kushta, J., Reale, M., and Ricard, D.: Mediterranean cyclones: Current knowledge and open questions on dynamics, prediction, climatology and impacts, Weather and Climate Dynamics, 3, 173–208, https://doi.org/10.5194/wcd-3-173-2022, 2022. a, b, c

Flaounas, E., Dafis, S., Davolio, S., Faranda, D., Ferrarin, C., Hartmuth, K., Hochman, A., Koutroulis, A., Khodayar, S., Miglietta, M. M., Pantillon, F., Patlakas, P., Sprenger, M., and Thurnherr, I.: Dynamics, predictability, impacts and climate change considerations of the catastrophic Mediterranean Storm Daniel (2023), Weather Clim. Dynam., 6, 1515–1538, https://doi.org/10.5194/wcd-6-1515-2025, 2025. a

Gill, A. E.: Atmosphere–Ocean Dynamics, Academic Press, San Diego, CA, ISBN 978-0-12-283522-3, 1982. a

Giorgi, F.: Climate change hot-spots, Geophysical Research Letters, 33, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006gl025734, 2006. a

Givati, A. and Rosenfeld, D.: The Arctic Oscillation, climate change and the effects on precipitation in Israel, Atmospheric Research, 132, 114–124, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2013.05.001, 2013. a, b

Goldreich, Y.: The climate of Israel: observation, research and application, Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0697-3, 2003. a, b, c

Good, S.: Global Ocean OSTIA Sea Surface Temperature and Sea Ice Analysis, EU Copernicus Marine Service Information (CMEMS), Marine Data Store (MDS), https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00165, 2022. a

Hannachi, A., Jolliffe, I. T., and Stephenson, D. B.: Empirical orthogonal functions and related techniques in atmospheric science: A review, International Journal of Climatology, 27, 1119–1152, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1499, 2007. a

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Hirahara, S., Horányi, A., Muñoz-Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Abdalla, S., Abellan, X., Balsamo, G., Bechtold, P., Biavati, G., Bidlot, J., Bonavita, M., De Chiara, G., Dahlgren, P., Dee, D., Diamantakis, M., Dragani, R., Flemming, J., Forbes, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A., Haimberger, L., Healy, S., Hogan, R. J., Hólm, E., Janisková, M., Keeley, S., Laloyaux, P., Lopez, P., Lupu, C., Radnoti, G., de Rosnay, P., Rozum, I., Vamborg, F., Villaume, S., and Thépaut, J. N.: The ERA5 global reanalysis, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803, 2020. a, b, c

Hochman, A. and Gildor, H.: Synergistic effects of El Niño–Southern Oscillation and the Indian Ocean Dipole on Middle Eastern subseasonal precipitation variability and predictability, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 151, e4903, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.4903, 2025. a

Hochman, A., Bucchignani, E., Gershtein, G., Krichak, S. O., Alpert, P., Levi, Y., Yosef, Y., Carmona, Y., Breitgand, J., Mercogliano, P., and Zollo, A. L.: Evaluation of regional COSMO-CLM climate simulations over the Eastern Mediterranean for the period 1979–2011, International Journal of Climatology, 38, 1161–1176, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5232, 2018a. a

Hochman, A., Harpaz, T., Saaroni, H., and Alpert, P.: The seasons’ length in 21st century CMIP5 projections over the eastern Mediterranean, International Journal of Climatology, 38, 2627–2637, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5448, 2018b. a

Hochman, A., Harpaz, T., Saaroni, H., and Alpert, P.: Synoptic classification in 21st century CMIP5 predictions over the Eastern Mediterranean with focus on cyclones, International Journal of Climatology, 38, 1476–1483, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5260, 2018c. a

Hochman, A., Mercogliano, P., Alpert, P., Saaroni, H., and Bucchignani, E.: High-resolution projection of climate change and extremity over Israel using COSMO-CLM, International Journal of Climatology, 38, 5095–5106, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5714, 2018d. a

Hochman, A., Kunin, P., Alpert, P., Harpaz, T., Saaroni, H., and Rostkier-Edelstein, D.: Weather regimes and analogues downscaling of seasonal precipitation for the 21st century: A case study over Israel, International Journal of Climatology, 40, 2062–2077, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.6318, 2020. a

Hochman, A., Alpert, P., Negev, M., Abdeen, Z., Abdeen, A. M., Pinto, J. G., and Levine, H.: The relationship between cyclonic weather regimes and seasonal influenza over the Eastern Mediterranean, Science of the Total Environment, 750, 141686, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141686, 2021a. a, b

Hochman, A., Rostkier-Edelstein, D., Kunin, P., and Pinto, J. G.: Changes in the characteristics of ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ Red Sea Trough over the Eastern Mediterranean in CMIP5 climate projections, Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 143, 781–794, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-020-03449-0, 2021b. a

Hochman, A., Marra, F., Messori, G., Pinto, J. G., Raveh-Rubin, S., Yosef, Y., and Zittis, G.: Extreme weather and societal impacts in the eastern Mediterranean, Earth System Dynamics, 13, 749–777, https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-13-749-2022, 2022a. a, b

Hochman, A., Scher, S., Quinting, J., Pinto, J. G., and Messori, G.: Dynamics and predictability of cold spells over the Eastern Mediterranean, Climate Dynamics, 58, 2047–2064, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-020-05465-2, 2022b. a, b, c

Hochman, A., Plotnik, T., Marra, F., Shehter, E.-R., Raveh-Rubin, S., and Magaritz-Ronen, L.: The sources of extreme precipitation predictability; the case of the ‘Wet’ Red Sea Trough, Weather and Climate Extremes, 40, 100564, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2023.100564, 2023. a

Hochman, A., Shachar, N., and Gildor, H.: Unraveling sub-seasonal precipitation variability in the Middle East via Indian Ocean sea surface temperature, Scientific Reports, 14, 2919, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53677-x, 2024. a, b

Hoskins, B. J. and Valdes, P. J.: On the existence of storm-tracks, Journal of Atmospheric Sciences, 47, 1854–1864, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1990)047<1854:oteost>2.0.co;2, 1990. a

Kara, A. B., Rochford, P. A., and Hurlburt, H. E.: An optimal definition for ocean mixed layer depth, Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 105, 16803–16821, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000jc900072, 2000. a

Kaspi, Y. and Schneider, T.: The role of stationary eddies in shaping midlatitude storm tracks, Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 70, 2596–2613, https://doi.org/10.1175/jas-d-12-082.1, 2013. a

Keller Jr., D., Givon, Y., Pennel, R., Raveh-Rubin, S., and Drobinski, P.: Untangling the mistral and seasonal atmospheric forcing driving deep convection in the Gulf of Lion: 1993–2013, Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 129, e2022JC019245, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022jc019245, 2024. a

Khodayar, S., Kushta, J., Catto, J. L., Dafis, S., Davolio, S., Ferrarin, C., Flaounas, E., Groenemeijer, P., Hatzaki, M., Hochman, A., Kotroni, V., Landa, J., Láng-Ritter, I., Lazoglou, G., Liberato, M. L., Miglietta, M. M., Papagiannaki, K., Patlakas, P., Stojanov, R., and Zittis, G.: Mediterranean cyclones in a changing climate: A review on their socio-economic impacts, Reviews of Geophysics, 63, e2024RG000853, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024rg000853, 2025. a

Kohonen, T.: The self-organizing map, Proceedings of the IEEE, 78, 1464–1480, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0925-2312(98)00030-7, 1990. a

Lelieveld, J., Hadjinicolaou, P., Kostopoulou, E., Chenoweth, J., El Maayar, M., Giannakopoulos, C. e., Hannides, C., Lange, M., Tanarhte, M., Tyrlis, E., and Xoplaki, E.: Climate change and impacts in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East, Climatic Change, 114, 667–687, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0418-4, 2012. a

Lionello, P., Malanotte-Rizzoli, P., and Boscolo, R. (Eds.): Mediterranean Climate Variability, Elsevier, Amsterdam, ISBN 978-0-444-52170-5, 2006. a, b, c

Ludwig, P. and Hochman, A.: Last glacial maximum hydro-climate and cyclone characteristics in the Levant: a regional modelling perspective, Environmental Research Letters, 17, 014053, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac46ea, 2022. a

Luo, D., Yao, Y., Dai, A., and Feldstein, S. B.: The positive North Atlantic Oscillation with downstream blocking and Middle East snowstorms: The large-scale environment, Journal of Climate, 28, 6398–6418, https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-15-0184.1, 2015. a, b

Martin-Vide, J. and Lopez-Bustins, J.-A.: The western Mediterranean oscillation and rainfall in the Iberian Peninsula, International Journal of Climatology, 26, 1455–1475, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1388, 2006. a

Muñoz-Sabater, J., Dutra, E., Agustí-Panareda, A., Albergel, C., Arduini, G., Balsamo, G., Boussetta, S., Choulga, M., Harrigan, S., Hersbach, H., Martens, B., Miralles, D. G., Piles, M., Rodríguez-Fernández, N. J., Zsoter, E., Buontempo, C., and Thépaut, J.-N.: ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications, Earth System Science Data, 13, 4349–4383, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-4349-2021, 2021. a

Palutikof, J.: Analysis of Mediterranean climate data: measured and modelled, in: Mediterranean Climate: Variability and Trends, edited by: Bolle, H.-J., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 125–132, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-55657-9_6, 2003. a

Price, C., Stone, L., Huppert, A., Rajagopalan, B., and Alpert, P.: A possible link between El Nino and precipitation in Israel, Geophysical Research Letters, 25, 3963–3966, https://doi.org/10.1029/1998gl900098, 1998. a, b

Raveh-Rubin, S. and Flaounas, E.: A dynamical link between deep Atlantic extratropical cyclones and intense Mediterranean cyclones, Atmospheric Science Letters, 18, 215–221, https://doi.org/10.1002/asl.745, 2017. a

Reale, M., Raganato, A., D'Andrea, F., Abid, M. A., Hochman, A., Chowdhury, N., Salon, S., and Kucharski, F.: Response of early winter precipitation and storm activity in the North Atlantic–European–Mediterranean region to Indian Ocean SST variability, Geophysical Research Letters, 52, e2025GL116732, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025gl116732, 2025. a

Redolat, D. and Monjo, R.: Statistical predictability of Euro-Mediterranean subseasonal anomalies: The TeWA approach, Weather and Forecasting, 39, 899–914, https://doi.org/10.1175/waf-d-23-0061.1, 2024. a, b

Redolat, D., Monjo, R., Lopez-Bustins, J. A., and Martin-Vide, J.: Upper-Level Mediterranean Oscillation index and seasonal variability of rainfall and temperature, Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 135, 1059–1077, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-018-2424-6, 2019. a, b

Rostkier-Edelstein, D., Kunin, P., Hopson, T. M., Liu, Y., and Givati, A.: Statistical downscaling of seasonal precipitation in Israel, International Journal of Climatology, 36, 590–606, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.4368, 2016. a

Saaroni, H., Halfon, N., Ziv, B., Alpert, P., and Kutiel, H.: Links between the rainfall regime in Israel and location and intensity of Cyprus lows, International Journal of Climatology: A Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 30, 1014–1025, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1912, 2010. a, b

Samuels, R., Hochman, A., Baharad, A., Givati, A., Levi, Y., Yosef, Y., Saaroni, H., Ziv, B., Harpaz, T., and Alpert, P.: Evaluation and projection of extreme precipitation indices in the Eastern Mediterranean based on CMIP5 multi-model ensemble, International Journal of Climatology, 38, 2280–2297, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5334, 2018. a

Seager, R., Naik, N., and Vecchi, G. A.: Thermodynamic and dynamic mechanisms for large-scale changes in the hydrological cycle in response to global warming, Journal of Climate, 23, 4651–4668, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010jcli3655.1, 2010. a, b, c, d, e

Seager, R., Liu, H., Henderson, N., Simpson, I., Kelley, C., Shaw, T., Kushnir, Y., and Ting, M.: Causes of increasing aridification of the Mediterranean region in response to rising greenhouse gases, Journal of Climate, 27, 4655–4676, https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-13-00446.1, 2014. a, b, c

Seager, R., Wu, Y., Cherchi, A., Simpson, I. R., Osborn, T. J., Kushnir, Y., Lukovic, J., Liu, H., and Nakamura, J.: Recent and near-term future changes in impacts-relevant seasonal hydroclimate in the world's Mediterranean climate regions, International Journal of Climatology, 44, 3792–3820, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.8551, 2024. a, b

Titchner, H. A. and Rayner, N. A.: The Met Office Hadley Centre sea ice and sea surface temperature data set, version 2: 1. Sea ice concentrations, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 119, 2864–2889, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013jd020316, 2014. a

Tootoonchi, R., Bordoni, S., and D'Agostino, R.: Revisiting the moisture budget of the Mediterranean region in the ERA5 reanalysis, Weather Clim. Dynam., 6, 245–263, https://doi.org/10.5194/wcd-6-245-2025, 2025. a, b, c

Treguier, A. M., de Boyer Montégut, C., Bozec, A., Chassignet, E. P., Fox-Kemper, B., McC. Hogg, A., Iovino, D., Kiss, A. E., Le Sommer, J., Li, Y., Lin, P., Lique, C., Liu, H., Serazin, G., Sidorenko, D., Wang, Q., Xu, X., and Yeager, S.: The mixed-layer depth in the Ocean Model Intercomparison Project (OMIP): impact of resolving mesoscale eddies, Geoscientific Model Development, 16, 3849–3872, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-16-3849-2023, 2023. a

Tzvetkov, E. and Assaf, G.: The Mediterranean heat storage and Israeli precipitation, Water Resources Research, 18, 1036–1040, https://doi.org/10.1029/wr018i004p01036, 1982. a, b, c

Vallès-Casanova, I., Adam, O., and Martín Rey, M.: Influence of winter Saharan dust on equatorial Atlantic variability, Communications Earth & Environment, 6, 31, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01926-2, 2025. a

Wang, W. and McPhaden, M. J.: The surface-layer heat balance in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Part I: Mean seasonal cycle, Journal of Physical Oceanography, 29, 1812–1831, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0485(1999)029<1812:tslhbi>2.0.co;2, 1999. a

Wills, R. C., Byrne, M. P., and Schneider, T.: Thermodynamic and dynamic controls on changes in the zonally anomalous hydrological cycle, Geophysical Research Letters, 43, 4640–4649, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016gl068418, 2016. a

Zittis, G., Almazroui, M., Alpert, P., Ciais, P., Cramer, W., Dahdal, Y., Fnais, M., Francis, D., Hadjinicolaou, P., Howari, F., Jrrar, A., Kaskaoutis, D. G., Kulmala, M., Lazoglou, G., Mihalopoulos, N., Lin, X., Rudich, Y., Sciare, J., Stenchikov, G., Xoplaki, E., and Lelieveld, J.: Climate change and weather extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, Reviews of Geophysics, 60, e2021RG000762, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021RG000762, 2022. a

Ziv, B., Dayan, U., Kushnir, Y., Roth, C., and Enzel, Y.: Regional and global atmospheric patterns governing rainfall in the southern Levant, Int. J. Climatol., 26, 55–73, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1238, 2006. a, b, c